VW vs. RAMBLER

VW vs. RAMBLER

In the late 1950s, two unconventional carmakers battled for a small market share. Only one survived.

By Cliff Leppke

Back in 1964, Car and Driver identified postwar vehicles that challenged the status quo — the Big Three. These “protest cars” had a sliver of the U.S. market. Their allure was their lack of conventional allure — style and performance were often jettisoned for a sense of individuality that was often “unjustifiable” by most “drivers’ standards.”

Back in 1964, Car and Driver identified postwar vehicles that challenged the status quo — the Big Three. These “protest cars” had a sliver of the U.S. market. Their allure was their lack of conventional allure — style and performance were often jettisoned for a sense of individuality that was often “unjustifiable” by most “drivers’ standards.”

The Volkswagen was, then, along with Rambler, the only protest cars in the “pink of health.” In fact, back in 1958 Foreign Car Guide considered the Rambler American a car of interest to the VW driver.

Between C&D’s April 1964 covers, its editors claimed they were overjoyed when a Rambler American road test confirmed the real basis for their prejudices against the American Motors’ aesthetic.

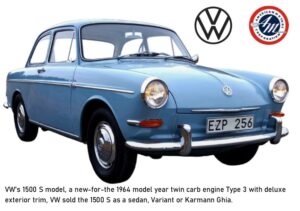

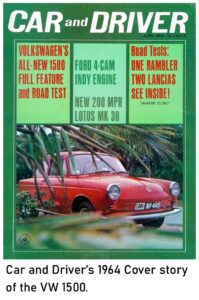

In contrast, its lengthy road report on VW’s 1500 S began with words we didn’t see in the Rambler road test: “We’ve seldom begun testing a car that we wanted to be good as badly as we wanted this one to.”

In reality, C&D was protesting VW’s decision to ignore the U.S. market for the 1500. Its April 1964 cover story explored why VW wouldn’t import the 1500 here and covered nine pages. C&D said it got an enormous number of letters from readers asking when or how they could get this VW Type 3, and the cover story claimed VW’s politics and global market manipulation forced Americans to buy 1200cc Beetles rather than the Type 3s they wanted.

That didn’t stop American VW fans from paying as much as $3,000 for a 1500 S Variant, nearly double the cost of a Beetle. C&D thought that price crazy, but that’s what some unofficial importers charged for VW’s Type 3 wagon. The Beetle had a robust gray market, too — C&D reported a six- or seven-month waiting list for Bugs at VWoA.

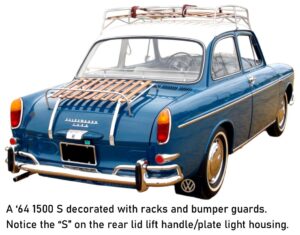

The 1500 S (for “Special”) had a dual carburetor engine with much more power than the earliest 1500 models. Also, and significantly, VW dressed up the exterior with front lid chrome and bright metal side trim. Note that the C&D cover story shows a normal (plain Jane), not S model Type 3, without the deluxe bright trim.

The 1500 S (for “Special”) had a dual carburetor engine with much more power than the earliest 1500 models. Also, and significantly, VW dressed up the exterior with front lid chrome and bright metal side trim. Note that the C&D cover story shows a normal (plain Jane), not S model Type 3, without the deluxe bright trim.

C&D editors focused on how much they wanted the marvelous quality and workmanship of a VW, the economy of the VW but with all those other things that made the Beetle problematic “fixed.” They said the Type 3 started out as the Porsche sedan you’ve dreamed of but ultimately, when pushed near its top speed, its rear-engine, swing-axle setup spoiled its potential as Juan Manuel Fangio material. Yet, C&D thought it would make a great economy car if the price were right.

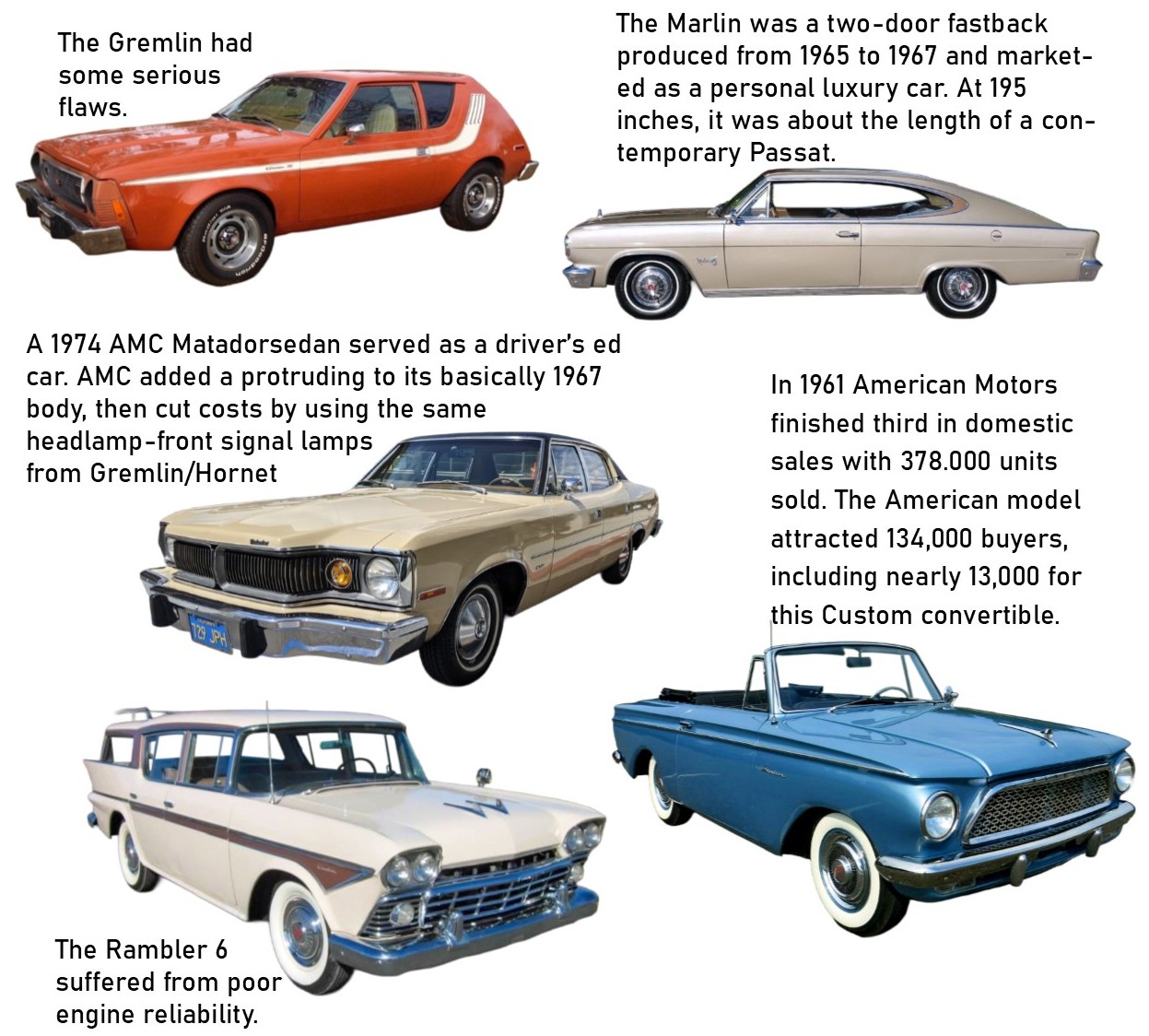

According to Car and Driver, Rambler had the blind luck of being unfashionably small at the dawning of the era when it became terribly smart to have an unfashionably small automobile. AM, as it was then known (and was later called AMC), produced what was regarded as “pretty dreary” cars. They had a host of didn’ts: didn’t handle well, didn’t fit drivers well, didn’t stop well, didn’t behave in the wind and didn’t become a joy to drive. Or, as C&D said, the improved 1964 American suffers from poor brakes, poor acceleration, too much wind noise, low resistance to crosswinds and an absolute lack of good handling. It was built for unimaginative people to drive to unimaginative destinations on straight, smooth roads.

While Car and Driver, which lambasted the VW due to its bad behavior on slick roads, wind sensitivity, its cramped confines or its mournful acceleration, realized what VW owners recognized: quality that led to vociferous Beetle loyalty. And you got standard bucket seats, four-on-the floor with synchronized first gear, relatively quick steering and a handiness at moderate speeds that could be imagined at a Porsche driving school.

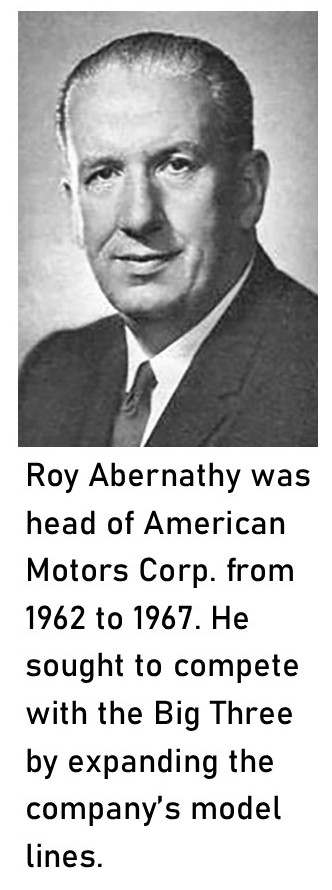

Not so the Rambler. C&D put Rambler’s chief, Roy Abernethy, on the William Jennings Bryan side of an automotive Scopes Trial. Rambler was against automotive evolution. And as we’d learn in other publications, AM tried styling itself as a savvy alternative to mainstream Detroit fashion but was often far too slow to significantly upgrade its product. Consumer Reports noted in 1971 that the Gremlin it ranked lower than a Super Beetle had vacuum wipers, an engine that dangerously stalled in right turns (a longtime AMC foible) and no first gear synchro.

I’ve thought about the differences between VW and AMC. I lived most of my life in Wisconsin, where American Motors, in Kenosha, south of Milwaukee, was the largest private employer. I wanted the hometown team to triumph. You just had to root for the underdog — not all that different, the underdog part, from VW.

But I wonder whether automotive journalists tell the AMC story well. They talk about cars as if they were playing with paper dolls. The dolls are pretty much the same, just put some fancy wrappers on them.

Then again, AM said its compact American wouldn’t be restyled annually to save people money … like another evergreen car. But it ate those words several times, turning the bathtub-like one into a rectangular one in 1961 and then completely redoing that homely runt into a smoother handsome-looking 1964 model, which got squared off a few years later.

Then again, AM said its compact American wouldn’t be restyled annually to save people money … like another evergreen car. But it ate those words several times, turning the bathtub-like one into a rectangular one in 1961 and then completely redoing that homely runt into a smoother handsome-looking 1964 model, which got squared off a few years later.

But let’s go below the surface. For 1966, AM’s ad agency, Benton & Bowles, ran an editorial-style ad in Life magazine. It covered a Chicago AM dealer convention, which focused on the “friendly giant killer” or Rambler. It was making a big change in automotive history by building quality in; not adding it on. Then, it presented four supposedly new models, which were embellishments on the previous year’s cars.

Popular Science reported that AM thought its sales slide in the mid-1960s was not due to vehicle styling, but instead the Rambler’s staid image. So, it revamped it. The ads got attention in Newsweek (Nov. 15, 1965) in an article titled “The Name Dropper.” AM claimed its cars beat rivals and named the rivals too — instead of the ubiquitous but fictional Brand X. Renault “showdown” did the same, comparing square-front Renault with the German sloped-hood car.

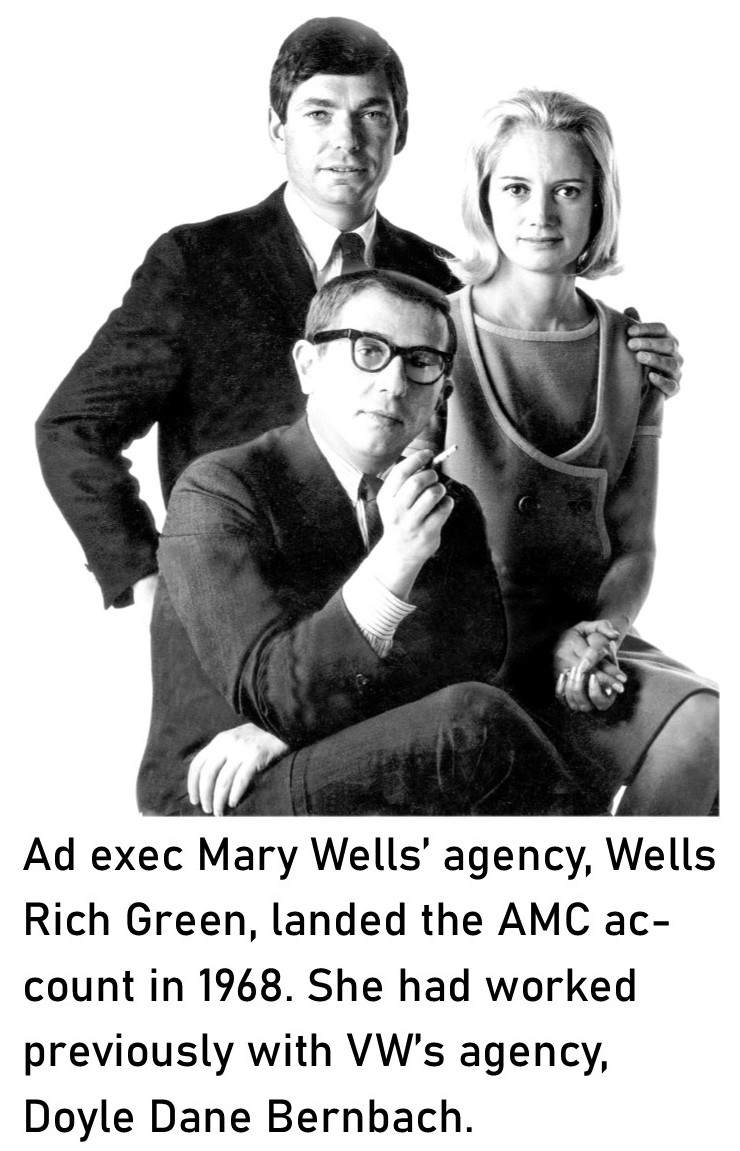

Jan Norbye, Popular Science’s automotive expert, blasted Rambler’s 1966 lineup for not installing swaybars, using inferior brakes and having dated torque-tube drives. Its Borg Warner automatic transmissions were tagged for rough shifting and lousy downshifts — or, as C&D noted, it took all of 10 seconds for the kickdown to be felt. It’s as if AMC put its resources into manufacturing a new image — see Mary Wells (former Doyle Dane Bernbach adwoman — right, VW’s agency), whose firm, Wells Rich Greene, landed the AMC account for 1968. AMC fancied itself as battling the Big Three on their turf when others, Toyota/VW, say, catered to the growing demand for subcompacts.

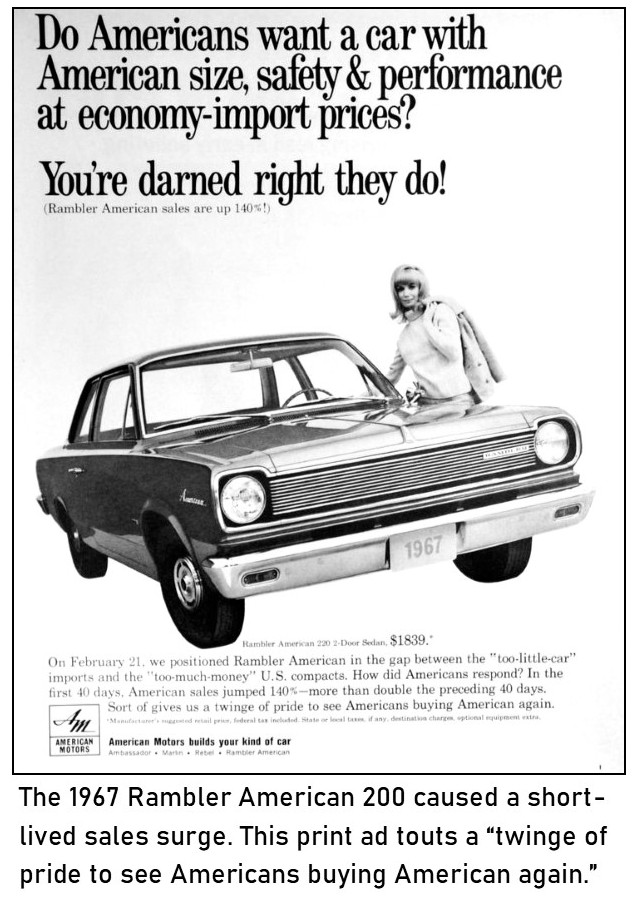

Surprisingly, despite AMC’s image makeover, it was the budget-priced import-fighting Rambler American 220 of 1967 that caused a short-lived sales stir. AMC couldn’t pump out enough of these Americans, but because AMC cut the dealer markup to lower the MSRP, the buyers expecting typical American-car discounts couldn’t get them.

Yet, as with VW’s True Volkswagen heritage kick, postwar Nash and later, after it merged with Hudson to form AM, often went back to inform its future. For 1950, it dusted off an old nameplate, Rambler, and applied it to its bulbous two-door 100-inch wheelbase compact car line, which eventually added a 108-inch wheelbase four-door. Then, it discontinued that model and replaced it with a freshly-styled 108-inch wheelbase Rambler in 1956, an intermediate.

In 1958, AMC stunned Detroit by reintroducing the old 100-inch wheelbase model: dubbed the American. And much like VW, it showed Detroit a thing or two about the kinds of cars Americans wanted — something sane during an era of outrageous excessiveness in Big Three cars. But underneath the “intermediate” Rambler 6 (later Classic), despite all its normalcy, the car was a mechanical disaster.

In 1958, AMC stunned Detroit by reintroducing the old 100-inch wheelbase model: dubbed the American. And much like VW, it showed Detroit a thing or two about the kinds of cars Americans wanted — something sane during an era of outrageous excessiveness in Big Three cars. But underneath the “intermediate” Rambler 6 (later Classic), despite all its normalcy, the car was a mechanical disaster.

The Rambler’s economy six, all 195.6 cubes of it, in OHV form — basically a flathead converted to OHV — had a host of durability problems, which cropped up when people drove it on modern interstates. Nevertheless, some interpret AMC’s longtime » use of this engine as proof of its iron-tough nature — much like VW’s 40-hp air-cooled engines, which while millions were served, tossed exhaust-valve heads into their combustion chambers.

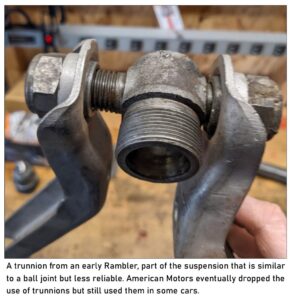

My father, his co-worker friend and a buddy from church all got late-1950s Ramblers. All encountered the same problems. The head gaskets failed due to “Siamesed” cylinders, which were too close for comfort. As Consumer Reports noted in its 1966 car buying guide, the OHV Rambler 6 AM used until the mid-1960s, had poor engine reliability scores for piston rings, valves and so forth. Plus AM’s front suspension was problematic, too. Hence, it dropped those late ’50s and early ’60s Ramblers from its desirable cars list.

To be fair, AMC improved its suspension by adding ball joints but still used pesky trunnions, too. The 1967 senior cars jettisoned AM’s torque-tube drive. AMC developed modern and durable engines and began buying its automatic transmissions from Chrysler. But slide behind the wheel of almost any AMC model, and you’ll discover a steering wheel you must hold like a poker hand. Seat adjustment, as C&D noted, was altogether inadequate.

To be fair, AMC improved its suspension by adding ball joints but still used pesky trunnions, too. The 1967 senior cars jettisoned AM’s torque-tube drive. AMC developed modern and durable engines and began buying its automatic transmissions from Chrysler. But slide behind the wheel of almost any AMC model, and you’ll discover a steering wheel you must hold like a poker hand. Seat adjustment, as C&D noted, was altogether inadequate.

My father rebuilt our Rambler wagon’s engine three times to reach 90,000 miles. That made our 1966 Bug seem positively durable in comparison. The Bug’s engine ate an exhaust valve — just saying better but not indestructible. The Rambler’s rear axle broke, the front suspension died young. None of these Rambler pioneers returned to their AM dealers for their next cars. In contrast, I knew a church pastor who traded in his Javelin on a Hornet Sportabout.

Regardless, I thought people who ridiculed AMC cars as “Kenosha vibrators” were biased.

Then, I drove a Matador during my driver’s ed class. I cannot say what I hated the most —

clumsy handling, slow steering, plasticky steering wheel, awkward driving position, flimsy interior trim or that AMC road noise. Plus, my father let me motor in our 1959 Rambler. Its road sense was dreadfully vague, certainly dull.

I wonder whether the Volkswagen story apes the AMC saga. In a sense, it does. VW then and now, as have others, dusted off old nameplates and put them on newer models. The New Beetle is the most famous — although VW “adopted” that Bug appellation, a vernacular description of its seminal sedan. The mid-’70s Rabbit returned for 2006. VW reintroduced the Euro Scirocco nameplate after discontinuing that line, but the third gen Ro wasn’t built on a prior Scirocco platform.

In Brazil, VW discontinued the Fusca, or Beetle, in 1986 and then brought it back in 1993. The EuroVan, discontinued in the States in the early 1990s, came back about four years later with a different engine, and yet a bit later with more power and premium-fuel appetite. Like AMC’s intermediate-size car-name parade, VW used three names — Dasher, Quantum and Passat — for one model.

At the MAMA Fall Rally, I found lots of name games. Ford’s Maverick truck dons its former compact car’s sobriquet and a turn-the-key ignition switch. Dodge’s Charger sports a once discontinued name. Toyota’s Crown revives a retired brand, and Acura brought back the Integra. And the Jeep Wrangler has the vibe of the AMC-built CJ-5.

Visit PBS.org to view the six-part documentary on the American Motors Corp., entitled “The Last Independent Automaker.” VWCA

Cliff Leppke | leppke.cliff@gmail.com

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE:

- FAVORITES FALL FEST: The Midwest Automotive Media Association performs its autumn exercises in suburban Chicago.

- BACK TO THE FUTURE: Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz are making a deliberate effort to re-discover their roots.

PLUS OUR REGULAR COLUMNS AND FEATURES:

- Small Talk – VW + Audi at a glance

- Retro Autoist – From the VWCA archives

- VolksWoman – Lois Grace

- The Frontdriver – Richard Van Treuren

- ID Insight – Todd Allcock

- Beetle World – Steve Midlock

- Editor’s Turn – Fred Ortlip

- Local Volks – Activities of VWCA affiliates

- Classified – . . . Ads from members and others

- Parting Shot – Photo feature