By Fred Ortlip

In a country badly polarized, many fulminated against a divisive law-and-order president who attacked the news media and called his supporters the “silent majority.” Racial upheaval helped stir a cauldron of protests in major cities, pockmarked by rioting, destruction and death. The president’s opponents had hoped that the approaching election would be a beacon for change.

But it wasn’t. That president was Richard M. Nixon, elected at the height of the tumult in 1968, and re-elected in a landslide in 1972, helped by the opposition Democratic Party in disarray and unnerved voters fearful that our democracy was crumbling.

Like many universities during this turbulent era, Bowling Green State University in Ohio was a campus embroiled in discontent over the Vietnam War, its decade-long U.S. involvement with no apparent end, and a president who had escalated bombing in adjoining Cambodia to unheard of levels.

Like many universities during this turbulent era, Bowling Green State University in Ohio was a campus embroiled in discontent over the Vietnam War, its decade-long U.S. involvement with no apparent end, and a president who had escalated bombing in adjoining Cambodia to unheard of levels.

The height of that discord took place 136 miles to the east of Bowling Green on May 4, 1970, when 28 members of the Ohio National Guard fired more than five dozen live rounds at protesting Kent State University students, killing four and wounding nine others. The students were protesting U.S. expansion into neutral Cambodia as well as the Guard’s presence on campus.

Soon after, Neil Young, part of Crosby Stills Nash & Young, wrote and composed the counterculture anthem “Ohio,” a song whose haunting opening guitar riffs and jarring lyrics were banned from AM radio playlists in parts of the country because of its anti-war sentiment:

Tin soldiers and Nixon coming,

We’re finally on our own.

This summer I hear the drumming

Four dead in Ohio.

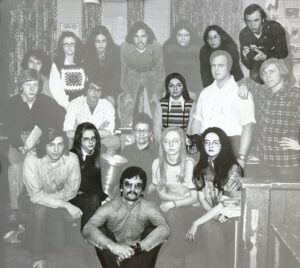

Fast-forward to January 1973, when more than 80 Bowling Green area war protesters, many poised to let their “freak flags” fly, prepared for a bus trip to Washington to join thousands from around the country descending on Washington for Nixon’s inauguration. BGSU’s sprawling University Hall, completed in 1915, served as the first-floor home to the campus newspaper and was as scruffy as some of its young BG News staff members who mulled covering the event.

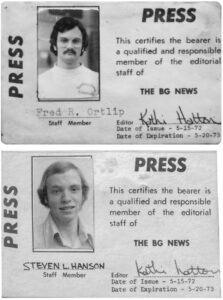

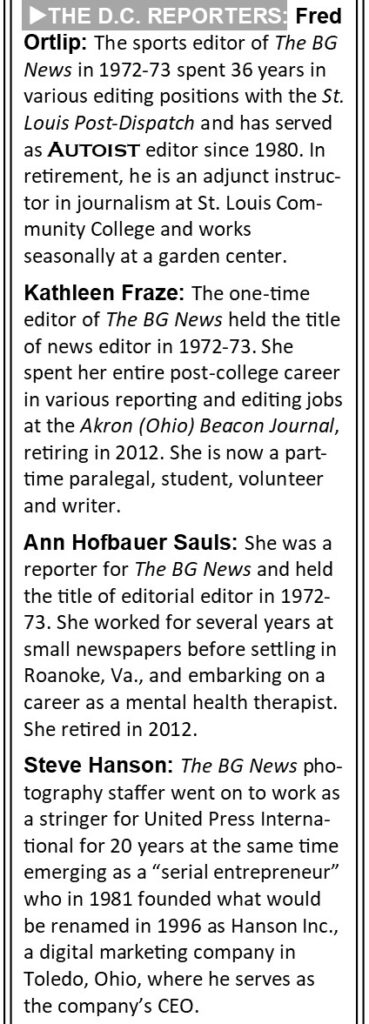

The editor at the time was Katherine Hatton and the faculty adviser was Emil Dansker. Reached earlier this year, neither remembered any detail about planning for the coverage. Neither did the photo editor, Marcy Lanzer Nighswander.

But photographer Steve Hanson says with a certain amount of confidence that the meeting must have happened on Thursday, Jan. 18, two days before the inauguration itself. He said Kathleen Fraze, who held the title of news editor, probably commenced the impromptu gathering among those who happened to be in the newsroom at the time, in effect anyone who wasn’t in class or tending to other important campus matters of the day, like napping.

“I was standing there, talking to Fraze, and it was like, ‘we’ll go cover this,’” Hanson recalled earlier this year. “Then there was this ‘how are we gonna get there — who’s got a car?’ … I think it was like a ‘let’s do it’ and we left on Friday.”

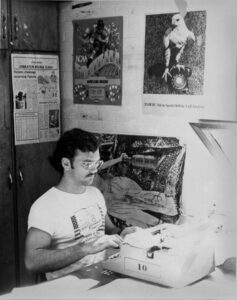

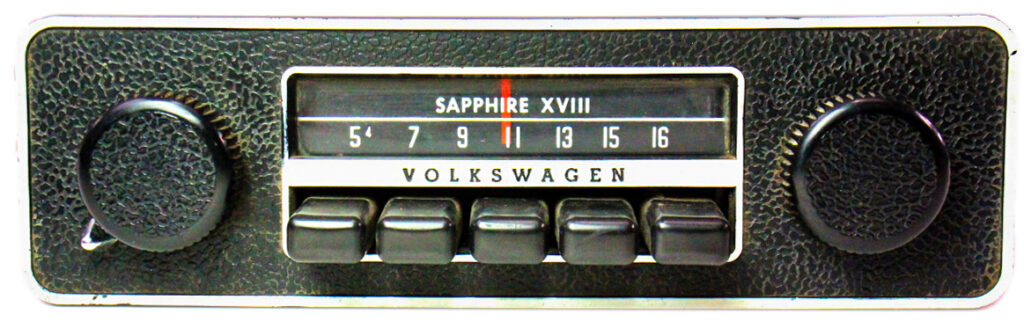

Turned out, I was the guy with the car, a 1971 Volkswagen Beetle, painted in a jolt of orange called Clementine, that an uncle had helped me purchase new 18 months earlier. As sports editor of The BG News, I sat in one of the corners of the newsroom and Hanson recalled my role. He said when the car question was raised, “somehow you either popped up or somebody went to you.”

Ann Hofbauer Sauls, the fourth designated staffer, doesn’t remember how she was picked but said in an interview, “It was just a fun idea. … I just said, ‘I want to go.’”

I have long lost all memory of the meeting but always assumed that someone had called out, “Who’s got a car that can get us from here to D.C. and back?” I was in the right place at the right time, as were those who would make the 530-mile journey: Fraze, then a senior from Massillon, Ohio, was 21; Hanson, a sophomore from Dayton, Ohio, was 19; and Hofbauer, a senior from Oregon, Ohio, was 21. I had just turned 22, a senior from Galion, Ohio.

We couldn’t have dreamed of the surprise coming our way.

In the dead of winter, with no idea whether any adverse weather lay ahead, this foursome would clamber into the Beetle to plod for more than eight hours across northern Ohio and the Allegheny Mountains via the Pennsylvania Turnpike to the nation’s capital for this historical event. The VW’s World War II-era technology was renowned for generating enough cabin heat to prevent frostbite, and as long as we descended one of many interstate downgrades, the Beetle’s 60-horsepower engine easily enabled us to hit and even surpass the 70 mph speed limit.

VW never made excuses for a ponderous 0-60 clocking of about 16 seconds, and even a print ad then acknowledged with a shrug, “It’ll pass most other cars on the road. Eventually.”

Of course, we knew we would be covering not the inauguration ceremony itself but the accompanying protests. What we didn’t know as were headed east on that Friday morning was where we were staying overnight. Toll-free phone numbers were not yet a thing, credit cards were rare and people typically didn’t make hotel reservations then anyway — thus, the “vacancy” or “no vacancy” signs that flashed in colorful neon. Sure, someone could have dialed directory assistance and asked for a Holiday Inn in a specific town in a Washington suburb. But we were college students on a mission and with little time to plan, apparently oblivious to the fact that many thousands would be descending on Washington and require sleeping quarters for at least a night.

One thing we apparently did have was ample cash. Hanson remembers a “stipend from The BG News,” and Fraze said, “I do think Emil scraped up $100 or so for our expenses. Heck, he might have shelled it out of his own pocket.” Dansker, who turned 90 in April, says he doesn’t remember. But chump change it definitely wasn’t: Factoring inflation, $100 would feel more like $585 today.

Hanson told me: “I remember the first shift, when we left, Kathy was in the right seat next to you. I was in the right seat in the back next to Ann. I remember because I had my gear, and I was fussing with it. And there’s not a lot of leg room in a Beetle, so we had to travel light. I probably erred more on the side of lenses and equipment versus clothing. But I do remember that you solo drove it coming and going.”

That was probably because the others lacked expertise with a four-speed manual transmission, but either way, I wasn’t going to let someone else drive my nearly new car. Or let Fraze and Hanson muck up the pristine interior with cigarette smoke. Fraze reminded me, “You did pull into a rest stop once or twice to let us huff and puff outside.”

The first leg of the smoke-free trip was otherwise forgettable, and as we approached the massive truck stop at Breezewood, Pennsylvania — two hours from the capital — the anticipation grew. Heading southeast through Maryland, signs for the D.C. suburbs began to appear. Gaithersburg, Rockville, North Bethesda. Where should we start looking for a place to stay?

Maybe we saw a billboard near Bethesda, but that’s where we veered off. And because we were four savvy college students on a mission — needing no more than one room and two beds — we found a hotel where the glow of the vacancy sign’s accompanying “no” must have been dimmed. In retrospect, what was a hotel clerk to think of these four bedraggled young people, given the concern locally of protests and potential rioting? Perhaps a displaying of press cards — they would have been difficult to forge then — and Hanson dangling his camera gear, a Nikon model FTN and its four lenses, were enough assurance that we weren’t going to trash the place.

Maybe we saw a billboard near Bethesda, but that’s where we veered off. And because we were four savvy college students on a mission — needing no more than one room and two beds — we found a hotel where the glow of the vacancy sign’s accompanying “no” must have been dimmed. In retrospect, what was a hotel clerk to think of these four bedraggled young people, given the concern locally of protests and potential rioting? Perhaps a displaying of press cards — they would have been difficult to forge then — and Hanson dangling his camera gear, a Nikon model FTN and its four lenses, were enough assurance that we weren’t going to trash the place.

We didn’t linger, refolding our tired bodies back into the Beetle for the 40-minute jog to the capital. On an evening in which the glitterati attended inaugural concerts and parties, four small-town Ohioans were on a wide-eyed observation cruise.

And soon to be in for a shock.

Fraze picks it up from here, in an op-ed piece she wrote in 1985 as the Akron Beacon Journal prepared to cover President Ronald Reagan’s inauguration. “I was not invited to Richard Nixon’s second inauguration,” she snarled. “Probably because of my jeans.” She noted that tens of thousands of outsiders, many like her, were watching the insiders that year.

She wrote further:

“As Nixon took the oath of office, [the outsiders] stood nose to nose in the numbing cold, waving their banners, hawking their anti-war buttons and chanting slogans until their throats were raw. They marched in outrage and some of them cried.

“But for us, the real confrontation between outsiders and insiders came much earlier — in an empty side street [the evening before], just blocks from the White House.

“We were crammed into a … Volkswagen Beetle, and we were tired and stiff from the drive. But we were celebrating because we had made it through the snow and the mountains and for one moment, the city was magical and it was ours.

“It was white monuments and white lights glaring against a cold black sky, and we gawked and forgot to be bitter and tough and politically aware.

“Until the sirens started, faint and irritating at first, then loud and jarring. The VW hugged the curb as a motorcycle cop whipped around the corner, then another cop, and another.

“Fifteen motorcycles sped by us, and then the cruisers, and then the first black limousine.

And then his limousine.

“The president slumped in the back, in his tuxedo, his face pale as he flashed past our headlights.

“If we had been generous, we would have said that the man looked tired.

“But we were less than polite.

“For us, the flamboyant motorcade in the middle of the night on a deserted street was a symbol of all that was wrong, and we howled and screeched in protest and jumped up and down in our seats until the little VW rocked drunkenly on its wheels.

“He slipped by us without a glance in our direction. We were insulted.

“The flashing red lights dimmed. The sirens faded.

“It was glaring white on black again. Silent and very cold.”

On viewing the motorcade, Hofbauer recalled: “When we realized what it was, we were just screaming. I always had the sensation that the little Volkswagen was just jumping up and down. We were howling, and we just drove right into it.”

I vividly remember the eruption at the instant I saw the presidential seal on the Lincoln Continental’s door. We had a front-row view, the first car among the several vehicles held up at the eastbound corner of Constitution Avenue and 17th Street, a baseball’s lob from the motorcade as it turned north onto 17th. Inside this counterculture Volkswagen, a symbol for many of the anti-war resistance, we might have felt a sense of pride that Nixon couldn’t have missed glimpsing our glow of orange had he turned his head only slightly as the motorcade rounded the corner.

In the interview, Hofbauer observed, “We had gotten closer to Nixon than most of the people at the inauguration.”

A long day was nearing its end. To paraphrase The Band’s lament in its 1968 hit “The Weight,” we were no doubt feeling ’bout half past dead as we pulled into Bethesda, at a place to lay our heads — albeit in tight quarters. And on Saturday, inauguration day, we made a smart decision.

Hanson confirmed Fraze’s memory of catching a bus to the capital: “We decided there was no way in hell we were driving there and trying to park,” he said. “I’m remembering the classic overhead storage bins, throwing the gear and stuff up there. And I remember looking out the windows when we came into the city, like, oh, my god, this is just amazing. … And we have no credentials, [just] our BG News press passes. And we’d just driven to D.C. on a lark in a Bug.”

And this was when we tried to set aside our personal opinions and embark on reporting the story as students aspiring to be serious journalists, the mantra we’d heard from Dansker, our adviser, and the other Bowling Green Journalism School instructors.

Wherever we arrived, we split up, agreeing to meet somewhere and at a specific time that no one now remembers.

Hofbauer recalls standing near a tree and seeing a line of police on horses. “All of a sudden, the horses turned toward my end of the street and began galloping in my direction,” she said. “I figured I could get up a tree if I had to.”

Fraze said: “I don’t remember ever being in any danger, but I do remember missing a confrontation around the corner somewhere and sniffing the tear gas dispersing on the wind. We must have had a very good plan on where and when to meet up again, because I don’t remember anyone missing the bus back to Bethesda.”

Though none of us recalls how we managed to reunite, Hofbauer noted, “It never even occurred to me that we wouldn’t be able to catch up with each other.”

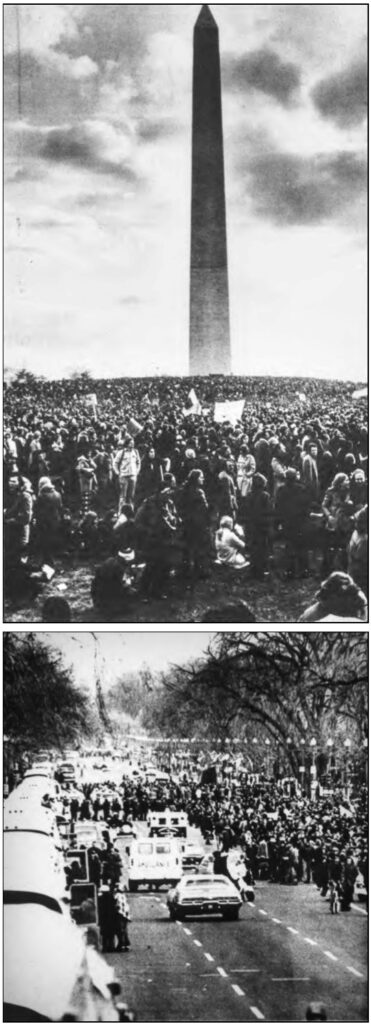

For The BG News, Fraze wrote three stories, including the protest roundup, noting that “National Park police reported about 60,000 persons faced extremely cold winds to participate in the half-mile march from the Lincoln Memorial to the Washington Monument.”

Two dozen of Hanson’s photos were published of the 20-25 rolls of Kodak Tri-X black-and-white film — at 36 images a roll — that he carried. Among his more jarring photos was a 15-foot tall papier-mâché depiction of a scowling Nixon with a crown, carrying the likeness of a bomb over his shoulder.

Under a dual-story headline titled “Not only the young protest war…” Hofbauer found Mat and Marie Kauten, 62-year-olds from New Hope, Pennsylvania, whose first demonstration in front of the White House was in the late 1940s, seeking amnesty for draft resisters, and that President Harry S. Truman had come out on one of the porches and thumbed his nose at them.

She reported: “They said they didn’t think their protests would end the war. But they said they believed they had to do something. ‘I just hope it makes him feel bad. I hope Nixon says ‘godammit’ when he sees it on television,’” said Mat Kauten as wife Marie stood nearby.

Hofbauer recalled: “I remember thinking they were so old, and I was so interested to be able to talk to them because they had been old hippies.”

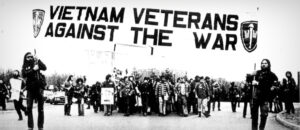

She also covered the Vietnam Veterans Against the War symbolically signing a peace treaty between the United States and North Vietnam.

I interviewed Leopold Geiger, a 74-year-old German immigrant who worked as a cabdriver in New York City. He said he had regretted volunteering for Germany in World War I. “I’m in favor of anything that’s good for the people,” he said. “War is naturally the worst thing for people.”

He had tied his American flag on an aluminum pole and fastened a black necktie at the top of the staff, unaware, he said, that the flag was actually upside-down, the traditional symbol of a country in distress.

“I carry this flag with the Stars and Stripes to reach more people,” Geiger said. “You reach more people and can appeal to them more by carrying the Stars and Stripes. Carrying the Vietnam banners and flags — that’s fascism. That just makes people more mad and alienates them.”

Ideally, we would have found Nixon supporters to interview, but this was a needle-in-a-haystack kind of protest, and the president’s supporters were called the “silent majority” for a reason. Fraze joked, “I don’t remember anyone protesting for Nixon or the war. They all got invitations to the inauguration.”

The New York Times reported that nearly 20,000 of the nation’s mostly influential Republicans watched the inauguration from the grandstands of the east portico at the U.S. Capitol with a scattering of Democrats. Two people among the demonstrators who filled two buses from BG to Washington contributed a story for The BG News from their perspective. The demonstrations were mostly peaceful. Fewer than three dozen people were reported arrested amid only minor scuffles between police and protesters.

At some point later that afternoon, our foursome magically reunited, caught a bus back to Bethesda and pointed the Beetle toward Ohio. Hours later, through the Pennsylvania darkness, Hofbauer called for the Beetle’s single-speaker AM radio to be silenced while she began transcendental meditation chants in the front seat.

We were, om-om-om, speechless.

“I actually did that?” she recalled with a laugh. “I was kind of new into doing it, so it was something I was committed to doing. One of the things they said was that people were less angry when they started doing transcendental meditation.”

Maybe the chill of the head wind was having its way with the Beetle’s tepid interior: Its windows were not only fogging up but freezing over. Steering with one hand and using a scraper with the other allowed me to keep the flat, up-close windshield acceptably clear as we drove through the night. We had plenty of work to do the next day, Sunday, for Monday’s work on Tuesday’s 16-page section, nine pages of which were devoted to the inauguration.

Though the Beetle had its limitations, it answered the challenge with aplomb, hauling a maxed-out load of adults and their gear more than 1,000 miles without a glitch.

Fraze summed up the experience: “We never thought we couldn’t do it. We were young and invincible, and righteousness was on our side. It was a great adventure, no one got hurt and no one was arrested.”

Things didn’t end so well for Nixon, who resigned the presidency in disgrace nearly 19 months later, as the Watergate scandal consumed his administration. And my Beetle would soldier on reliably until 1976, when it was traded in for an all-new water-cooled Volkswagen called the Rabbit. ![]()

Fred Ortlip | VWAutoist@icloud.com

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE:

- TIGUAN SEL PREMIUM R-LINE: For about $40,000, this might be all the SUV you need.

- LONGTIME MEMBER DIES: Maurice Goldsteiin, a second-generation family member of the VWCA, dies at age 68.

- 1974 THING: This quirky throwback Volkswagen makes people smile wherever it goes.

PLUS OUR REGULAR COLUMNS AND FEATURES:

- Small Talk – VW + Audi at a glance

- Retro Autoist – From the VWCA archives

- Letters – . . . and e-mails

- The Frontdriver – Richard Van Treuren

- Parting Shot – Photo feature

- Local Volks Scene – A snapshot of local chapter activities

- VW Toon-ups – Cartoon feature by Tom Janiszewski

LOGGED-IN MEMBERS CAN SEE THE ENTIRE AUTOIST ISSUE BY CLICKING ON THE “AUTOIST ARCHIVE” OPTION UNDER THE “AUTOIST” TAB.