RATIONALIZING GREATNESS

RATIONALIZING GREATNESS

Decades of deep affection belied Beetle’s legendary reputation

By Cliff Leppke

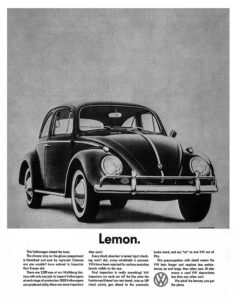

“Mad Men,” a fictional TV show about admen, often evoked 1960s verisimilitude. Within the program’s make-believe chromium jungle on Madison Avenue was a sense of historical accuracy. The show’s characters discussed actual period products and ad campaigns. In one notable episode, staffers from the Sterling Cooper agency scrutinized a VW print ad dubbed “Lemon.” Agency art director Salvatore Romano argued that the VW had “no chrome, no horsepower.” It was “foreign.”

“Mad Men,” a fictional TV show about admen, often evoked 1960s verisimilitude. Within the program’s make-believe chromium jungle on Madison Avenue was a sense of historical accuracy. The show’s characters discussed actual period products and ad campaigns. In one notable episode, staffers from the Sterling Cooper agency scrutinized a VW print ad dubbed “Lemon.” Agency art director Salvatore Romano argued that the VW had “no chrome, no horsepower.” It was “foreign.”

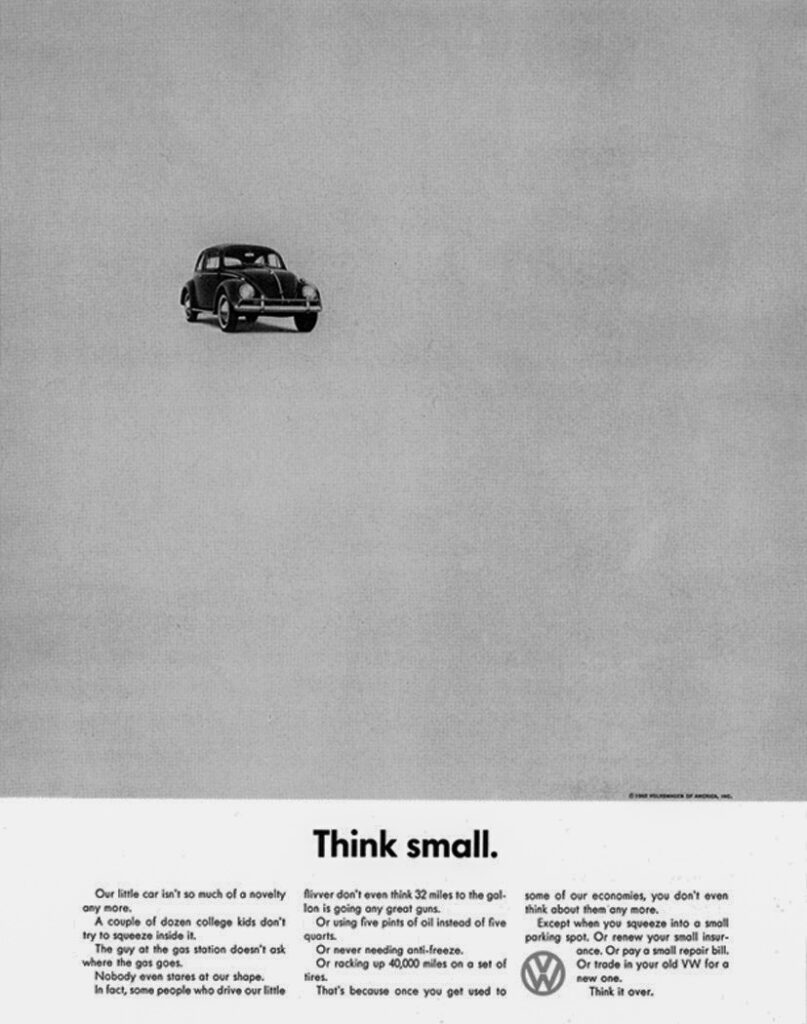

Romano recollected an earlier “Think Small” ad — a half-page ad and a contrarian full-page buy. “You could barely see the product,” he said. In contrast, junior accounts executive and social-climber Pete Campbell says he thinks “it’s a great angle. … It’s funny, I think it’s brilliant.”

In the end, master creative guru Donald Draper, played by Jon Hamm, says, “you can say what you want. … I don’t know what I hate the most, the ad or the car. … Love it or hate it, we’ve been talking about it for the last 15 minutes.”

In a sense, fiction tells a truth. Americans have been talking about VW’s Bug or Beetle for generations. All rather remarkable for a car that racecar driver Wilbur Shaw thought so ugly no one would want to drive one. The initial enthusiasm for the later New Beetle only added to the car’s American profile. And we’re reliving the VW retro theme again with the ID. Buzz.

The seminal VW’s popularity makes it a convenient historic prop. The irony is this mass-produced car with a Nazi past engenders profound individualistic affection. Clearly the car’s meanings aren’t embedded in the car itself. It was received with a malleable sensibility — the typical American Beetle buyer was middle-class, suburban, college educated — and selected it as a sensible second car. In contrast, California Kustom Car fanciers repurposed it as a potent Cal Look sled while a counterculture of post-materialists and post-hedonists (hippies, say) embraced the Bug in their rebellion against suburban conformity — a contradiction. Nevertheless, flower power needed a four-wheeled prop.

The seminal VW’s popularity makes it a convenient historic prop. The irony is this mass-produced car with a Nazi past engenders profound individualistic affection. Clearly the car’s meanings aren’t embedded in the car itself. It was received with a malleable sensibility — the typical American Beetle buyer was middle-class, suburban, college educated — and selected it as a sensible second car. In contrast, California Kustom Car fanciers repurposed it as a potent Cal Look sled while a counterculture of post-materialists and post-hedonists (hippies, say) embraced the Bug in their rebellion against suburban conformity — a contradiction. Nevertheless, flower power needed a four-wheeled prop.

Almost from the car’s American arrival, people wanted to know why the People’s Car was the People’s Car. It seemed capable of embedding itself into various cultural stews, especially in its most important export market — the USA. In contrast, European nations with established domestic carmakers didn’t embrace the VW with the same gusto as America. The Brits, French and Italians, while VW curious, weren’t nations where the evergreen VW was a sales sensation.

Back to the past

Foreign Car Guide’s 1958 article by Al Outcalt probed postwar automotive and social phenomenon: “The Case of the Cherished VW.” He said VW’s slogan claiming “Owning a Volkswagen is like being in love” sounded “silly — perhaps even ludicrous.”

The evidence, however, showed VW owners didn’t find anything silly about their affections for the small car. A few months before the article, claimed Outcalt, a disgruntled man agreed to let his wife have the house, the furniture, the children and most of his money — provided he could keep the family VW.

And a 17-year-old girl had recently bought her first car, a Volkswagen, and after six months admitted frankly to her friends that she was in love for the first time — with her VW! A farmer notified the police that his wife had run off with another man in the farmer’s VW. He didn’t want the police to bring his wife back. All he wanted was his VW back!

And a 17-year-old girl had recently bought her first car, a Volkswagen, and after six months admitted frankly to her friends that she was in love for the first time — with her VW! A farmer notified the police that his wife had run off with another man in the farmer’s VW. He didn’t want the police to bring his wife back. All he wanted was his VW back!

A typical VW owner exhibited a strangely tender sentiment toward his car. Outcalt claimed a New Yorker, who was driving his third Volkswagen, was asked what he liked about his car. His answer was simple: It’s the first car I’ve ever had that I felt really understood me. Skip expensive psychotherapy, the VW relieved more than gas pains.

Meanwhile, the Volkswagen Club of America was cited as surveying more than 2,000 members on what they thought of their Volkswagens. The answers read like a long love poem. One “girl in California” called her VW her “pride and joy.” A bachelor in Pennsylvania frankly admitted that “at times, I almost wish I could take it to bed with me.” Whew!

Psychologists, Outcalt wrote, looked at motivational research. He said these tender feelings for 1,600 pounds of steel, glass, rubber and magnesium were often attributed to the car’s easy-to-drive nature, its gear-shifting fun or how little it cost to run were rationalizations. The reasons given for liking a car were excuses for “embarrassing affections for an inanimate object, almost a fetish.”

Outcalt dug more deeply into this topic and how the VWCA offered a form of camaraderie for thousands who shared attitudes toward the VW.

Bug taps into America’s motoring romance

Almost from its inception as a consumer good, the automobile has been linked to romance. Take the popular 1905 song “In My Merry Oldsmobile.” It turned the curved-dash motorized buggy into a courting car. The chorus says a lot: “Come away with me Lucille in my Merry Oldsmobile. … Down the road of life we’ll fly … to the church we’ll quickly steal, then our wedding bells will peal, you can go as far as you like with me, in my merry Oldsmobile.” Hot dog!

Other peons to pulchritude or phallic high-octane aphrodisiac motoring range from “Rocket 88” to the tempting “Pink Cadillac.” Others extolled the hidden potency of the “Little Deuce Coupe,” “409,” “Fun Fun Fun” (in a Thunderbird) and “Mustang Sally.”

Other peons to pulchritude or phallic high-octane aphrodisiac motoring range from “Rocket 88” to the tempting “Pink Cadillac.” Others extolled the hidden potency of the “Little Deuce Coupe,” “409,” “Fun Fun Fun” (in a Thunderbird) and “Mustang Sally.”

In contrast, the Playmates recorded a novelty hit that countered the horsepower race. In “Beep Beep,” the underdog 1950s Nash Rambler keeps pace with a Cadillac driver who feels his finned fantasy, the first love of 20 million motorists (said a 1953 Caddy ad) wasn’t a car to scorn. The song’s ever increasing tempo had Nash’s diminutive Kenosha, Wisconsin, compact keeping up with the fabulous V-8 Detroit dishpan.

These popular tunes show Americans can love almost any motorized chariot. I suspect some might find Edsels and Pontiac Aztecs at a drive-in under neon, gleaming beauties. But it was the VW Beetle that struck many observers as antithetical to the American sense of auto-erotic playthings. This made the car’s popularity worthy of scrutiny.

Outcalt concluded the Beetle’s affections fit three categories: the American love of discovery; we want to be pioneers, not slaves, to pushbutton madness, an American tribute to the intelligence and common sense of the buyer, who doesn’t want to waste money on a 12-miles-per-gallon gas-guzzler and finally, and most importantly for Outcalt, it’s a revolt against the heavily chromed, fully equipped longer new car painted in at least two colors and occasionally three.

The VW became a reverse status symbol in 1950s speak. It was conspicuous but inconspicuous consumption. The VW owner, in a sense, said he rejected every principle of the American auto industry, which we could summarize as dynamic or forced obsolescence. Detroit’s annual new-car makeovers and ever increasing vehicle size and engine horsepower were wasteful. In sum, VW’s car represented the joy of discovery, the mark of a shrewd buyer and a symbol of revolt. And it happened to be, in its moment, a nicely made automobile.

Decades later, Bernhard Rieger’s The People’s Car: A Global History of the Volkswagen Beetle re-examined the car’s longtime American success story. The VW owed its international appeal to corporate initiatives and just as importantly to the protracted processes of consumer reception and appropriation that reshaped its meanings in surprising and lasting ways.

VW became an ambassador of the German Federal Republic. It came from a nation previously not known for its automotive exports. By 1963, VW shipped 55% of its annual output to destinations beyond West Germany. Many of these 620,000 cars went to the Land of Liberty. At its peak, about 40% of Wolfsburg’s output arrived at U.S. ports.

VW became an ambassador of the German Federal Republic. It came from a nation previously not known for its automotive exports. By 1963, VW shipped 55% of its annual output to destinations beyond West Germany. Many of these 620,000 cars went to the Land of Liberty. At its peak, about 40% of Wolfsburg’s output arrived at U.S. ports.

Unlike the United Kingdom, where the VW was not a player, Americans welcomed the car with far more enthusiasm. Its commercial success in the U.S. established Volkswagen as a global automotive player.

The car acquired a new identity Stateside that it didn’t possess in its homeland. In Germany the car was ubiquitous — a solidly middle-class Volkswagen, representing automotive normalcy, a step up from bubble cars. In contrast, Americans saw an unusual car, which they dubbed the Beetle or Bug. Its technical features, size and shape set it apart from orthodox American vehicles.

Most profoundly, many Americans thought the VW was cute. It wasn’t threatening. Sports Car Illustrated’s artwork, by Bob Weber, reveals the same truth as John Keats’ “Insolent Chariots.” Weber, in “SPVW: The saga of the Beetlewagen” (circa November 1958), shows a small MG next to a menacing American sled with lances for its bumpers and tall bat-wing rear fins. A later page depicts one fin shown a full-page tall, illuminated as if it were a drag strip’s light tree.

Detroit’s fashion was outrageously wasteful. Or as the author Van Lesley says, “the most irritating thing, as any owner of The True Automobile knows, occurs at stoplights, when the Smart Aleck Detroit Owner leans over, sneers at you, races his motor … and then says, ‘Think you got a hot one there, huh?’ The male import small-car owner is treated like a child driving an underdeveloped toy.

The Bug’s cuteness was relative. Whereas the typical American sedan was finned and later panned for its excessive length, appetite and tinsel, the Bug was small and round. Renault’s soft-but square Dauphine, a late-1950s VW rival with its cheerful “beep, beep” TV ads, didn’t engender the same long-term feelings as the VW.

One reason could be the perception that the VW was crafted by fastidious Germans, led by GM-trained Heinz Nordhoff, who made quality control an obsession. Moreover, the seminal VW earned a reputation for going where other cars couldn’t. The VW, furthermore, famously touted its service and parts network. Unlike, say, the pint-sized Crosley car or Kaiser’s spartan Henry J, the VW wasn’t an automotive orphan.

One reason could be the perception that the VW was crafted by fastidious Germans, led by GM-trained Heinz Nordhoff, who made quality control an obsession. Moreover, the seminal VW earned a reputation for going where other cars couldn’t. The VW, furthermore, famously touted its service and parts network. Unlike, say, the pint-sized Crosley car or Kaiser’s spartan Henry J, the VW wasn’t an automotive orphan.

VW’s incredible growth and public acceptance surprised many automotive observers as did its American advertising. Volkswagen, with its Third Reich roots, ironically hired Doyle Dane and Bernbach, a New York ad agency founded by Jewish Americans. Two of its clients were Israel’s El Al Airlines and the country’s Tourist Office.

Its ads further embellished the car’s ability to break away from mainstream American automobile norms. When DDB used its Madison Avenue ads in Germany, however, its characterization of the car as unpretentious or small didn’t strike West Germans as surprising or unusual. DDB later developed a German campaign with the phrase “it runs and runs,” which became everyday German talk about the car as a symbol of the Federal Republic’s postwar normality and stability.

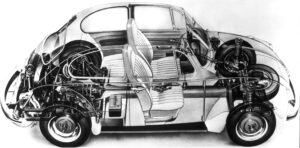

Volkswagen’s cheerful auto was not all unicorns and lollipops. It had serious warts. In its October 1966 road test of the 1300cc Beetle, Consumer Reports began its analysis with a paragraph that cut to the point: the VW’s habit of resisting change had been carried too far. CR said, “the Volkswagen ‘beetle’ (sic) has long been reputed to be something of a vehicular nonpareil — cheaper to buy and maintain, more fun to drive and easier to maneuver in congested traffic, and more practical for use as a commuter-suburban runabout than any other automobile.”

Although many called it fun, CR wrote, driving the Beetle required constant attention. “While it maneuvers more nimbly in moderate-speed traffic than most other cars … high speed maneuvers alter that picture. … With its tail-heavy weight bias and rear swing axles, the 1300 will go into an oversteer condition when cornered hard and do it suddenly enough to require skilled correction. On slippery surfaces or if one fails to maintain the correct tire pressures, the point at which tricky behavior can be expected lowers. Add to these factors the car’s directional instability under windy conditions and the car’s overall handling must be rated poor.”

The car, despite many heating system improvements, was always bedeviled with an inadequate heater. At low speeds, when you needed a good defroster, the car didn’t have an auxiliary fan to provide air flow. The Bug’s shape restricted interior room, and the car’s two stowage spaces weren’t as useful as competitive cars. The front trunk was small and the area behind the front seats was awkward to load through the vehicle’s doors.

The car, despite many heating system improvements, was always bedeviled with an inadequate heater. At low speeds, when you needed a good defroster, the car didn’t have an auxiliary fan to provide air flow. The Bug’s shape restricted interior room, and the car’s two stowage spaces weren’t as useful as competitive cars. The front trunk was small and the area behind the front seats was awkward to load through the vehicle’s doors.

In an August 1954 VW road test, Road & Track said the “biggest objection to the VW is its oversteering characteristic. This is the tendency (a very strong tendency) for the rear end to swing outwards, in a fast turn, to the point that the car wants to take the path of an ever tightening spiral. … With experience, the enterprising driver can ‘set up’ the correct drift angle for going through a fast corner. … It’s challenging. … An unexpected turn, or some emergency, demands extra skill or experience or both.”

VW, over the years, tamed the Bug’s stinger. The 1967 model had a wider rear track, front sway bar, relaxed rear torsion bars and a rear Z bar. These parts came from the brand’s Type 3 line. Then for 1969, VW completely redesigned the manual transmission VWs with double-jointed rear axles, eliminating the nasty rear-axle tuck-under. For the 1971 Super Beetle, with its bigger trunk, a new front suspension system further reduced the car’s tricky behavior. Nonetheless, contemporary reports said the VW, while improved, had been bested by a host of newer small cars with fewer vices.

My own experience with VW’s air-cooled vehicles is mixed. I might have loved in 1975 the 1300cc car’s bucket seats, four-on-the-floor shifter and easy clutch operation. In contrast, I learned to hate the car, too. This teenage driver entered a very sharp corner at night going too fast and experienced the rear-axle hopping effect of our family’s 1966 Bug. I nearly rolled the car. I intuitively stomped on the brakes, which only added to the drama, as this shifts weight forward, further letting the rear axles tuck under while skidding sideways.

This VW education led me to seek a less difficult-to-handle car. I bought a used Fiat but discovered parts and service for it far worse than I expected. So, I bought a 1966 Bug for myself, drove it for a few months and replaced it with a 1972 Squareback. This car was better behaved in wind or on twisty roads. Plus, it had a safer steering column, less vulnerable gas tank, more secure door latches and stouter wiper arms. Its cargo capacity and good fuel economy served me well, although rust, ignition and front brake problems made what should have been a reliable car a problematic one.

This VW education led me to seek a less difficult-to-handle car. I bought a used Fiat but discovered parts and service for it far worse than I expected. So, I bought a 1966 Bug for myself, drove it for a few months and replaced it with a 1972 Squareback. This car was better behaved in wind or on twisty roads. Plus, it had a safer steering column, less vulnerable gas tank, more secure door latches and stouter wiper arms. Its cargo capacity and good fuel economy served me well, although rust, ignition and front brake problems made what should have been a reliable car a problematic one.

While the VW dealer replaced the Squareback’s rusted heat exchangers, I drove a 1978 VW Rabbit. This test drive proved nothing short of astonishing. The Rabbit went faster, held its place on the road and didn’t require the air-cooled car’s constant driver attention. The wake of a semi didn’t bother it, either. VW’s Rabbit made me feel like Mario Andretti, not a Malaise Era victim.

I was hooked. VW’s new-generation of front-drive water-cooled cars convinced this “traditional VW driver” to seek something different, such as a Dasher wagon he test drove. He later got a Volvo, another Squareback (still has that car), a Toyota Corolla and eventually a Scirocco.

The other love VW

Surprisingly, my winter car, a bronze 1984 VW Scirocco, evokes tender affection, if not love, when parked in a postwar suburban home’s driveway.

George, a nearby neighbor, is just one of several people who’ve got a Scirocco story. What’s interesting to me is it’s the sad looking bronze VW that engenders affection, not the vehicle ahead of it, which wears its original Mars Red paint — a 1983 Wolfsburg Edition Scirocco. Perhaps Mae West was wrong; you cannot have too much of a good thing!

George says the car reminds him of high school, when the cops busted him, interrupting his dalliance with another student inside VW’s sin-bin coupe. He wishes the car didn’t have such large windows. He didn’t say a thing about lovemaking gymnastics in this VW’s tight cabin. I was afraid to ask. Yet, the wedge-like VW still evokes fond memories.

George is so smitten with VWs, he became a member of the Milwaukee Area Volkswagen Club. He invited me to the club’s Volksfest at a nearby Old Heidelberg Park’s beer garden. I saw a cornucopia of VWs, some hopped up and others chopped up. Show winners drove Beetles, Rabbits, Squarebacks, CCs, Golfs, Corrados and Buses. It seemed like anything donning or had donned a VW badge is adored.

These affections for VWs old and new wouldn’t have been possible, according to Rieger, if the venerable Beetle had been a one-hit wonder from Wolfsburg. VW’s situation in the early 1970s, as was West Germany’s, was nothing short of do or die — the press called Wolfsburg a “crisis center.” VW’s reliance on the outmoded Beetle drove the company into an automotive cul de sac.

When Toni Schmücker became VW’s chairman in early 1975, a transition VW called the Golf Generation, it cut production costs by offering workers severance packages and bet the farm on the recently introduced Golf.

Within two years, VW produced 1 million Golfs, creating a profitable new “miracle from Wolfsburg.” This unexpected turnaround ultimately led to VW’s decision to discontinue Beetle production in Germany. Alas, VW’s improved fortunes in its homeland wasn’t shared at its American operations, where Beetle-model sales skidded from 405,615 units in the 1970s to 19,245 in 1977. In the US, where the Golf was marketed as Rabbit, sales in 1977 were 149,170, indicating VW dealers’ sales volume had significantly declined despite the feisty new subcompact’s playful nature.

Of Beetles new and old

Of Beetles new and old

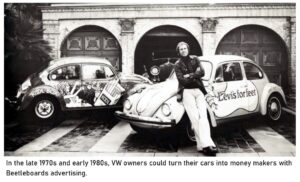

The Beetle mystique led VW to do something remarkable. It introduced a retro vehicle branded as the New Beetle. Some might recall Sun Country and Golden Beetle as two stabs at selling Mexican Beetles in Reagan-era USA. So, there was a precedent for probing consumer demand for another Beetle-like VW.

VWoA simply didn’t have a star car with the Beetle’s commodity lifespan. That said, a GTI driver might beg to differ. Nonetheless, no VW model sold more than 100,000 units Stateside in one model year since 1974 except the Rabbit, which peaked at 214,835 in 1979.

The surprising result was a global titan of a carmaker developed a Beetle-like Concept 1 designed by Americans James May and Freeman Thomas shown at the 1994 Detroit auto show. Concept 1 triggered a flood of press attention, prodding VW to turn that concept into a car for American drivers. In the end, Germany gave it the green light. The car, however, was further developed and manufactured on a new Golf platform at VW’s Mexican plant.

Rampant enthusiasm

The New Beetle made its carefully orchestrated debut at the 1998 North American International Auto Show. Speeches by Ferdinand Piëch and other VW executives and a cheering crowd of often jaded journalists resulted in rampant enthusiasm for the triple-arch-bodied car. VW said it increased New Beetle production to meet higher than expected demand.

In 1999, VWoA sold about 84,000 of these retro-themed cars. Six years later, despite adding convertible and turbocharged models to the line, sales tapered off at 36,339.

When the retro vehicle reached Germany months after its USA rollout, it did not create the same stir that made it instantly famous across the Atlantic. My informal poll of New Beetle drives revealed some who were passionate about the car’s styling inside and out. It democratized design. Others weren’t as enthusiastic, complaining about the vehicle’s electrical and mechanical troubles. And some traded their cars in for something with a bigger trunk, bigger side-view mirrors and less expansive dashboards. One meteorologist bought one, dubbed it the weather Bug, and months later traded it in on a Jetta.

Sales figures in Germany did not approach the heights of New Beetlemania in the USA. It didn’t represent a Teutonic comeback car. One reason is simple. VWAG did not need to stage a comeback — its Golf, for example, was popular. One Berlin newspaper caught the feelings for the retro Bug in Germany. It categorized the New Beetle as an inconsequential fun car: “Nobody needs it. … It wasn’t reasonable.”

VW is a global carmaker. Its wares have taken on strange trips in the various markets where VW sells or manufactures cars. While you’ll read many tributes to the adorable VW Beetle in the Autoist, you should think about cultural reception and the motor vehicle.

Americans have a romance with motoring. The affection for the Beetle is often nostalgia, a yearning for yesterday’s VW enhanced by amnesia. The good parts are potent in many a VW lover’s memory, but nostalgia often smooths over the disruptions of our lived experiences then and now. ![]()

Cliff Leppke | leppke.cliff@gmail.com

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE:

- GARAGE MAHAJ: After three years of bureaucratic delay, a car palace rises in California.

- TIMELESS JOURNEY: Can 1957 and 1964 Beetles owned for decades by one enthusiast reach immortality?

- SECOND LIFE: A once stolen 1973 standard Beetle continues to thrive for more than two decades with its second owner.

- OFF-ROAD READY: VW doesn’t do pickups or pickup-themed SUVs. This Lexus makes the case that it should.

PLUS OUR REGULAR COLUMNS AND FEATURES:

- Small Talk – VW + Audi at a glance

- Retro Autoist – From the VWCA archives

- The Frontdriver – Richard Van Treuren

- ID.Insight – Todd Allcock

- Editor’s Turn – Fred Ortlip

- Local Volks – Activities of VWCA affiliates

- Classified – . . . ads from members and others

- Parting Shot – photo feature