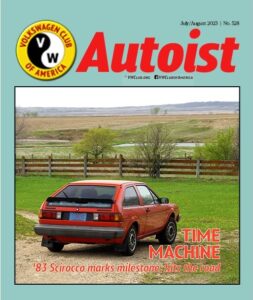

Marathon Scirocco

Marathon Scirocco

40-year-old VW tackles a 4,000-mile adventure

By Cliff Leppke

In early May, I woke my 1983 VW Scirocco from its winter hibernation, checked its tire pressures and soldered a bad electrical connection at its instrument cluster’s voltage regulator, which solved low temp and fuel-gauge level issues.

These were the opening steps to what would be a top-to-bottom crisscross of America covering 4,000 miles in which the Scirocco’s odometer would roll past 352,000 miles, its tachometer pointing toward 3,000 rpm while its 1.8-liter engine pulled me steadily at 70 mph.

From Milwaukee, I veered toward Paducah, Kentucky, to visit with auto writer Jules Stayton and her husband, who served me grilled bratwurst.

From there, my destination was my brother’s place on Florida’s Space Coast: Melbourne. He wanted to show me his Sunshine State income tax-shelter. I refilled the Scirocco in Paducah at 11 p.m, zipped through the glittering Music City and then east of Chattanooga, where I pulled into a ledge-like rest area for shuteye having covered some 275 miles.

Sorry, Holiday Inn, my VW’s right front seat reclines, converting into a lumpy bed. My rejuvenating layover — lulled to sleep by the din of nearby diesel engine clatter — went well until intense sunlight turned my auto into a hothouse shortly before noon, still in sync with my normal sleep cycle.

I resumed my diagonal route through Georgia, slipping through Atlanta’s wide thoroughfare. Slowed by construction backups, I arrived in Melbourne about 28 hours after I left Milwaukee.

On the agenda, a weekend of bicycling, a break from Milwaukee’s chilly weather and left-foot physical therapy. Then, I’d head back to Milwaukee and direct my wheels toward the Leppke farm in Carrington, North Dakota, with a pause near Minneapolis, where my sister’s family resides.

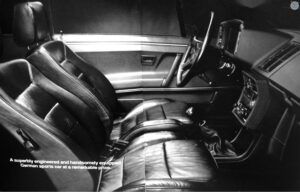

Whether it’s my DNA or some kind of primordial petroleum-age ooze, I find piloting a 1983 Wolfsburg Edition Scirocco transcendental. Sorry, Henry Thoreau, VW’s sports coupe is my Walden’s Pond—suspended on 14-inch Michelins. A mono wiper clears the pockmarked picture window. There’s something about tire patter song, this car’s languid comportment, the Teutonic din of its 1.8-liter mill and the cabin’s subdued rush of air while in flight. It melts time and space — an automotive fun-size Snickers.

Its hot-wind name suggests the romance of the open road, a conveyance to exotic lands and that analogue feedback dialed out of the digital-everything world. It’s a Dr. No car. No power steering, no cruise control, no turbocharger, no USB, no airbags, no ABS, no ESP, no hydraulic clutch and no digital music player. Yet, it’s a yes car, VW’s Medi-car, a mechanical-feeling salve to a person who is weary, trapped in a 40-hour workweek of computer screens, keyboard, software, graphical interfaces and internet connections.

The irony, of course, is the Scirocco and its driver are captives — routes aren’t free or open but rather prescribed by highway engineers, accountants, lawyers and politicians — hemmed in by the slight, white lines of the not so free, freeway.

Many have written about motoring. Get your kicks on Route 66. I have. These days, you’ll hear odes extolling electrified touring, charging networks and how to become the Columbus of recharging: the vehicle itself, the driver and its passengers.

You’d expect your correspondent, who’s published scholarly papers on roadside architecture, to focus on the shifting taste or lack thereof in the built environment nestled along our nation’s Eisenhower-era planned arteries. Instead, I present the narrative complexity of a public radio station’s pledge drive. Why? My highway haven is my longtime companion. A device discussed in the Autoist not once but multiple times over three decades.

My motoring manner, moreover, is out of sync with the usual notion of the fabled road trip. It’s like a Mars Red-eye special. I’m a shift worker; nighttime is my primetime. The Scirocco lets me travel during the dark side, when traffic is lighter and your vistas are murky silhouettes punctuated by neon or electronic billboards. My path is illuminated by H4 lamps. Toggle switches flank the RO’s flood-lighted instrument panel like an Art Deco Zenith Stratosphere radio. The oil temp, oil pressure and volt meter gauges reside in a console ahead of the shift lever.

I suspect my mode of transport might not seem appealing. It has a pre-history, a parallel practice employed by my late father, Elton, meant to maximize uninterrupted traveling. My folks woke us up before dawn, put us back to sleep in a 1967 Ford Country Sedan’s aft pew, and headed out into the darkness.

I suspect my mode of transport might not seem appealing. It has a pre-history, a parallel practice employed by my late father, Elton, meant to maximize uninterrupted traveling. My folks woke us up before dawn, put us back to sleep in a 1967 Ford Country Sedan’s aft pew, and headed out into the darkness.

His brood snoozed, while he sat on the front-bench seat’s left side. Because his progeny slept, traffic jams were few and the sun didn’t bake our rolling greenhouse without A/C my father found his kind of bliss. When he needed a break, my mother slid behind the wheel of a massive station wagon with a manual transmission, manual steering, manual brakes and a service manual.

Sometimes the Ford was loaded with a party of five, a Ward’s Sea King aluminum boat clamped on its roof, and a stout custom-built pop-up camper hitched to the car’s rear. We didn’t stop for fast or medium-speed food. My mother stocked the cooler with sustenance, often doled out as we rode. Highway signs of the roadside life — near Route 66 in Illinois — sirens seductively enjoining us to stop at Funk’s Grove’s Maple Sirup, Dixie Truckers Home, Steak ’n Shake, Lincoln’s sites and White Fence Farm were curiosities we didn’t explore. I notice there’s Henry’s Rabbit Ranch near Staunton Illinois. It’s punctuated with, I’m not kidding, VW Rabbits. Finally, a warren worth seeing.

We stopped for fuel, utilized waysides, or checked out Illinois’ I-55 modernistic brick-clad toilet building covered by a dramatic concrete form in a safety rest area — SRAs are what the interstate planners dubbed these rest areas, meant for safer motoring.

I’ve met a scholar who’s an expert on these expressway parks. The story behind these places, some sensationally liberated from period architecture, others stylized to reflect regional tastes, tells us a lot about where we’ve been as a nation and where we’re headed.

Our pilgrimages avoided roadside commercial entertainments. Our in-car activities were playing cards, auto bingo and road-sign word games. We were pilgrims in the sense that we found new highways, such as I-55, escaping the stoplights on Route 66. We discovered that our side of the monotonous wide lanes, with limited access mowed down my great-grandmother’s place in Minneapolis or my mom’s grandparents’ spread outside of St. Louis. What we lost, in my father’s opinion, we got back: virtual high-speed efficiency — a quicker way to get there, even if there was longer there.

Fast-forward to today. You’ll find my way across America’s highways, the paradise of dimmed dashboard illumination and the Scirocco’s oversized guiding wheel, strapped into a contoured bucket seat with a foam wedge placed atop the parking brake lever as a center armrest, a curiosity perhaps or just plain and about as appealing as wending your way through the waivers you must sign in order to drive on a racetrack.

The purple mountains of Tennessee are inky black. Their inclines require you to squish the long pedal or downshift to fourth. The lines guiding my route resemble an Olympic Tartan track. The hurdles are truck-tire carcasses littered throughout America’s midsection, and any one of them could hobble. You dodge them without the cheering spectators. Moreover, the tractor trailers (semis) pose hazards. Their heights are incompatible with motorcars. The appearance and experience of our motorways look nothing like the sleek, uncluttered park-like renderings promoting postwar urban and rural renewal.

Because I’m a night rider, I experience the 24/7 lifestyle of truck stops and the glow of semis lit like Christmas trees. Tennessee, at night, is a massive semi parking lot stretching the entire I-24 corridor. There was a time when 24-hour, pump-it-yourself fuel wasn’t the norm — truck stops were an exception.

Much like a racecar crew, I must balance the number and timing of pit stops, seeking speedy low-cost refills. My range, therefore, is either how far the Scirocco’s 10.6-gallon tank will let me go (315 miles puts the gauge into the red zone) or short of that, low-priced fueling meccas, places where I don’t have to contend with, say, Minnesota’s frontage highways, which twist your mind with their pretzel logic.

That’s the gas part. For food, I’ve got bagels nestled behind the front seats, granola bars, water and trail mix.

March of dimes

It turns out I traveled 3,975 miles, consumed 118 gallons of fuel, paid $378 for it, and averaged 33.8 miles per gallon. My math is fuzzy because at least one pump wouldn’t pop out a receipt. I haven’t refilled the car’s tank since returning home, and my brother treated me to gas at a Florida Costco — the price was about 40 cents cheaper per gallon than other places. I added one quart of oil. My gas bill was just below 10 cents per mile, including Costco’s tab.

While in Florida, my brother Gary and I mounted bicycles and rode about 15 miles the first day, 42 miles the second day (rain dampened that ride) and 35 miles the last. Besides the opportunity to explore this part of Florida, Gary had another trick up his short-sleeved jersey: he let me experience a 21st-century carbon-fiber frame Trek Domane SL 7 bike, lightweight wheels, tubeless tires, electronic shifting and hydraulic disc brakes. The first ride helped me master ski binding-like clipless bike pedals. You place hardware on your cycling shoes, snap it into the pedals and twist your foot sideways to release.

Electronic shifting, programmed to eliminate drive chain crossing, is the DSG of cycling. I performed most gear changes with two tiny buttons tucked behind the right brake lever. In addition, this bike’s effective braking system, tested on a bike path where a pedestrian stepped in front of me, works. The bike lifted its rear wheel, but I modulated the binders preventing a header. This cycle moves!

Lisa, my brother’s wife, treated us to a poolside, Italian-style dinner featuring her family’s favorite pasta sauce recipe. So, while I cooked up a storm on the bicycle, she did the same in the kitchen. One thing I noticed in Melbourne: lots of new concrete-block house subdivisions with reinforced garage doors. New building codes might improve the odds you’ll weather a major storm. I noticed none of the new developments with their branded entrances, directly interconnects with the other. You must use a trunk highway to get around, which could cause future traffic jams.

I headed back to Milwaukee driving north to Jacksonville, westward from there and then north to Atlanta. I reached Kentucky, when vivid lightning, my need for sleep and sheets of rain suggested I find the next rest area. I did. Hours later, I was back on the road. I ran into Chicagoland traffic jam and roughed up pavement. The Skyway, Dan Ryan, Kennedy, Edens and the Tri-State directed toward my old Milwaukee home.

A day later, I headed to Minneapolis where my sister, Barb, prepared sous vide salmon. This vacuum-sealed meal in a pouch reminded me of the early 1970s Banquet Cookin’ Bag meals. Fast food, meet sous vide slow food. Barb’s creation was fantastic. The next day, I headed west, into the sun, toward Carrington, arriving by dinnertime. My mother prepared roast beef.

I took my mom to Grace City (population 53) for Mother’s Day. There’s a postwar-era high school building now known as the Schoolhouse Cafe. Its rectangular form has several original items from its glass-block windows, decorative brick patterns and a flat roof. This is yesterday’s school of tomorrow, low-slung largely unsung with class photos and athletic trophies.

I found unexpected farm chores due to wet weather. The barn and its lower-level workshop had standing water. Family photos from 1947 show my grandfather employed a 1937 D-Series 1.5-ton six-wheel International truck to move and dump materials he used to build the barn and a house. And yet another photo features a 1927 Buick converted into a tractor — both the truck and that car are in the cattle shed. I don’t know whether they designed the barn’s foundation to manage water and frost. I discovered several vintage automobile headlights, though.

These relics have an uncertain future — everything must go. My mother plans to auction off my father’s expansive motoring/farming/electronics museum. I’d like to finish one of my dad’s restoration projects, or select, say, my grandparent’s 1938 Ford Tudor as a future project — one I currently neither have the room to store nor body shop willing to mend its busted body. There’s a 1972 VW Squareback, a 1966 Bug and an entire hayloft section filled with VW suspensions, engines, transmissions, wheels and body parts.

My trek home took less than 12 hours covering about 700 miles. I departed NDak with the RO’s air conditioner chilling, but a pneumonia front in Milwaukee — at least a 20-degree drop in one hour — meant my very last leg of the trip required me to turn on the heater. The 40-year-old Scirocco let me crisscross America rolling the odometer to just short of 352,000 miles. ![]()

Cliff Leppke | leppke.cliff@gmail.com

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE:

- 4 FINALLY ARRIVES: The wait lasted 11 months, and VW’s new is exceeding expectations.

- LAMENT OF A BEETLE OWNER: Historic run of a classic automobile couldn’t last forever.

- A NEW BEETLE OWNER’S YEARNING: Wouldn’t it be wise for VW to produce a third version?

- GROUNDBREAKING DECISION: How VW’s move to adopt fuel injection I the 1960s changed automotive history.

PLUS OUR REGULAR COLUMNS AND FEATURES:

- Small Talk – VW + Audi at a glance

- Retro Autoist – From the VWCA archives

- The Frontdriver – Richard Van Treuren

- Local Volks – Activities of VWCA affiliates

- ID.Insight – Todd Allcock

- Classified – . . . ads from members and others