What’s a Classic?

In the car collector scene, the shapes of things that caught our eye weren’t always ‘iconic.’ How ad puffery made us think they were.

By Cliff Leppke

The year’s end is a moment to reflect on the past. Many media outlets trot out their top 10 lists, markers of the year that was. Then, we greet the New Year with resolutions. While this latter ritual might help kickstart a hobby, improve health or heal human relationships, most promises end up in the same metaphorical dustbin as holiday gift wrappings or tree tinsel.

I cannot do much about our customs or institutional practices, but I can discuss several trends. Sorry, no awards, no contests and no clever English composition tricks. Instead, I’ll talk about one perplexing part of the collector car scene. Then, I’ll go back 60 years to a moment when big things changed due to a small car.

Collector car talk clutters any online vehicle search. Hagerty Insurance, for instance, tracks the collector car scene. Day-by-day we hear which cars are hot or not. These predictions often say more about those who write these forecasts than the data supporting them. It’s like a TV game show where contestants place their winnings at risk in order to win the motherlode. This frenzy distracts us from the non-monetary pleasures of car collecting.

Then there’s exaggeration. Have you noticed Hagerty’s online scribes describe nearly every car as a classic? Or that everything that rolled on wheels during the 1970s was Malaise-era trash? All two-door closed autos are coupes? And VW built its American success with only two vehicles — the Bus and Beetle?

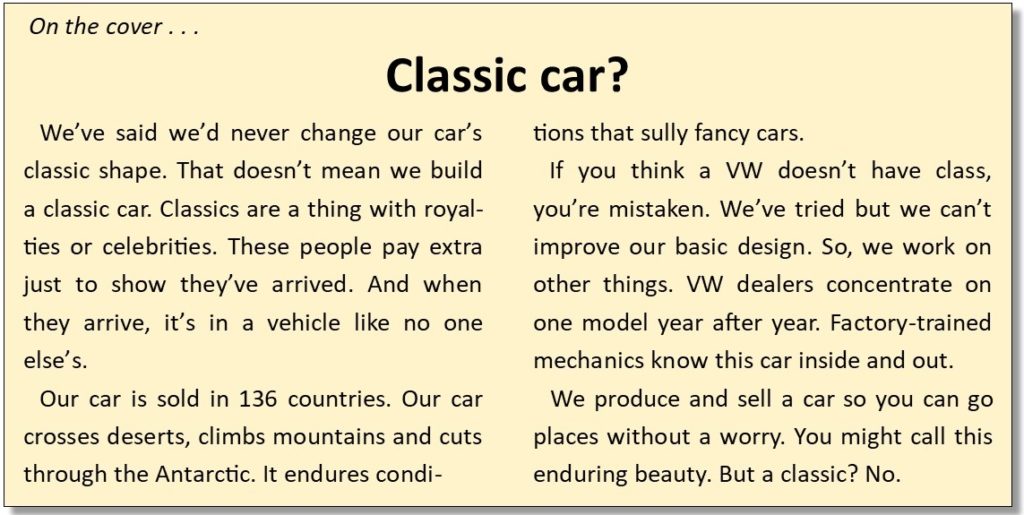

I suspect Ford’s 1975 American Granada is a classic due to its hood ornament, iconic due to its Mercedes-style grille and antique due to its age. Get real. Classic, as an automotive moniker, shifted from its foundation story. According to the Classic Car Club of America, which takes credit for coining “classic car,” a classic is a fine vehicle, often coach-built, made between 1915 and 1948. The CCCA, furthermore, created an approved list of bona fide classics. Those who formed the CCCA, in the early 1950s, celebrated vehicles newer than those cherished by the Antique Automobile Club of America.

Classic, however, as a noun or adjective for car has liquidated — as linguists say it. An example in brand names is word Kleenex when referring to any facial tissue or Xerox (the copy machine) as a verb for making copies. Collector-car insurance or state licensing cover a broader range of “classic” vehicles. And in popular use, classic modifies nearly any older car but usually describes vehicles of interest due to their design, marketing, engineering, or history. Thus, the CCCA now uses a capital C Classic or Full Classic to steer us toward its sanctioned list.

I’d say the Karmann Ghia is close to the CCCA’s definition of classic, but the made-for the-millions Beetle is not.

Iconic is another slippery word, likely not trademarked for automotive purposes. It’s overused. How about sui generis — one of its kind, unique in a class by itself? Consider signature for material artifacts created by a master. Remember the famous VW slogan “2 Shapes Known the World Over”? It’s shapes not icons. Although one must admit the Coke bottle shape and the Bug’s silhouette are iconic.

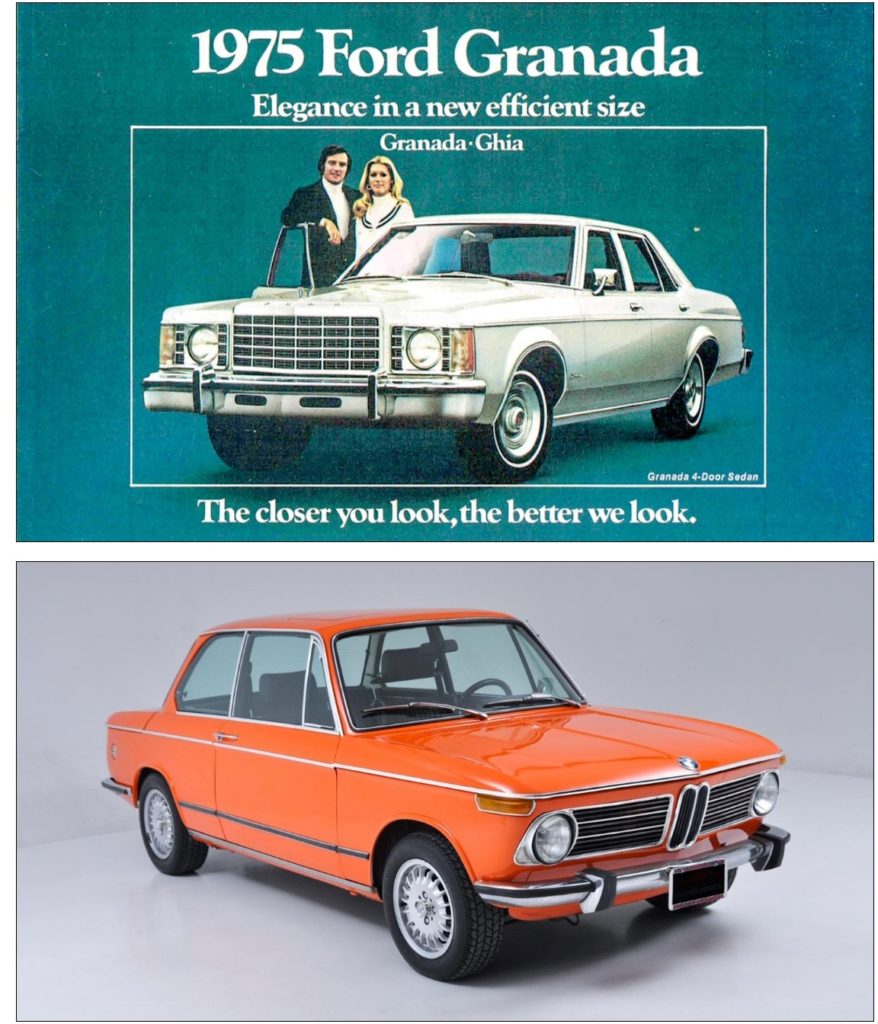

Where did the doors go?

What a body! Describing automotive bodies is problematic. These days it seems one just counts side apertures. If it’s got two doors, it’s a coupe. When there are four, it’s a sedan. The two-door sedan has vanished from automotive parlance. Yet, some of the most popular cars in the USA were two-door sedans. A good example the prewar Ford. A “Tudor” was by far its best-selling model. VW’s two-door sedan Beetle, likewise, sold in the millions. Its Karmann Ghia is the coupe. And yes, VW parts outfits sometimes call the Bug a coupe. Historically, that’s wrong. BMW’s 2002 archetypical sports sedan is yet another. Its Karmann-built 2000 C/CS is the coupe.

I see several semantic snags. One is we’re trapped in the past. We use horse-drawn carriage lingo or human-powered conveyance nomenclature for the horseless carriage. The other is a reduction in new vehicle styles. Our “eyes” no longer see what’s on wheels due to today’s truncated vehicle-type lineups. VWoA no longer sells two-door Jettas or Golfs; there’s nothing like the Ghia or Scirocco. In fact, 2020 marks the end (for now) of two-door VWs in America and the convertible, too.

There was a time when many carmakers offered a two-door coupe (some were hardtops without B pillars). Coupe often designated a body with a shorter top. Rear headroom was tight. Sometimes this roof was lower too. During the 1970s, Chevy Monte Carlos with their long side doors, padded tops and opera windows were hot stuff. Ugh!

Some writers argue two-door vehicles don’t make sense. Why would anyone buy a car where it’s difficult to reach the rear seat? (Driven a three-row crossover lately?) Yet, well designed two-door vehicles are a tall-guy’s salve. We prefer pushed-back B pillars, easy front-seat access and better shoulder belt fit. Sometimes you get stouter bodies, lighter weight and shorter wheelbases.

Get which GTI?

Accuracy is problematic. One example is Hagerty’s piece by Andrew Newton on the VW GTI. He pegged the roomier 1983-1992 Mk II GTI, as a 1980s favorite you should buy. It’s illustrated with a Mars Red Mk I GTI.

Perhaps the mad rush to generate buzz via web-based or social-media content leads to careless errors. It appears, based on reader comments about wrong GTI model years, that those who create this content play fast and loose with evidence or are simply flummoxed by it. Hagerty’s editors should correct their work. The outfit hired a bevy of capable people.

What’s wrong? Besides the flubbed photo, there’s a model-year error. While VW unwrapped the second-gen Golf GTI in January 1984 (1984 model year), our American-made Mk II GTI arrived for 1985. It won Motor Trend’s 1985 Car of the Year Award. The European, Golf, however appeared in August 1983 (1984 model). I applaud Newton for mentioning VW’s affordable fun car. Sometimes there’s a place in our driveways for Teutonic temptation for thousands less than dialing 911. But let’s get the facts straight.

Have sympathy. Most English-language VW model catalogues are British publications — even on the web. They speak to what’s seen in Europe, not the States. If you don’t live and breathe a particular marque here and abroad, you won’t capture the nuances of globalization.

Another problem is context. Sharp-tongued scribes present, say, vintage car ads interpreting what they mean without examining where they were published, who created them and how they were received. Contemporary writers gush, missing the textual play (how the ads converse with others) or whether admen or the public thought these now vintage ads were, gasp, awful. “Bewitched” and AMC’s “Mad Men” explored ad-aided persuasion. Why don’t ad commentators employ interpretive tools from these fictional portrayals?

Instead, you get the sense people blindly accepted advertising puffery completely brainwashed by Fireball engines, Gyroscopic rides and Magic Mirror finishes. They didn’t. Consumers mistrusted advertising practices. Admen also complained. Take Stan Freberg. In Green Chri$tma$, he satirically blasted outrageous postwar advertising tropes. Freberg also created his “honest” ad agency, which got his seal (the animal) of approval.

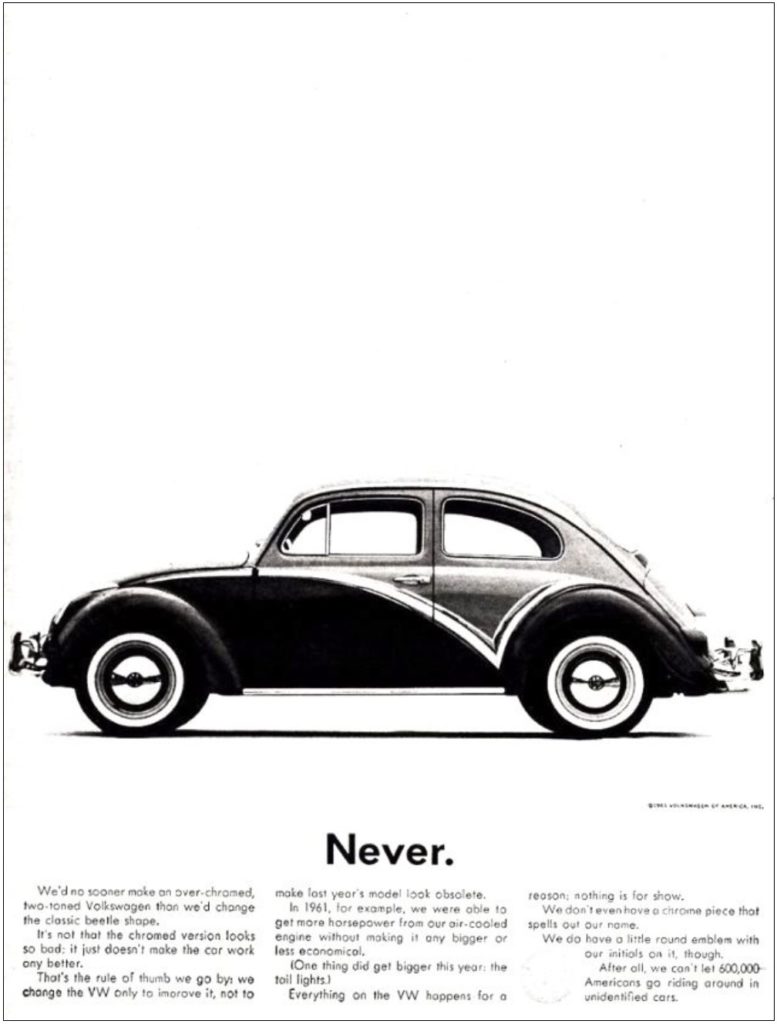

VW’s one-time ad agency, Doyle Dane Bernbach, also mistrusted conventional advertising — part of the larger postwar culture critique called “mass society.” It generated the “new advertising,” which attacked deceptive old advertising. Instead of concealing the processes of persuasion, DDB came out and told readers VW wanted to sell cars and make money. It admitted VW’s products weren’t perfect. It even showed dented cars, flat-tire cars and sometimes just the tire tracks.

It took the mass society problem seriously. For example, DDB’s creative work contained hip rebukes of TV programs and their ads — decades before Tina Fey’s fast-paced “30 Rock” sendup of GE’s management of NBC. “The Big Plateau” parodied besmirched, scandalous game shows. A 1968 VW Beetle spot pitted a frumpy shoemaker “Gino” against the temptation to climb to the top of the pyramid. The game-show host gave him 10 seconds to identify the 1968 VW’s changes. (OK, Bug fans start counting!) As the clocked ticked, the frumpy guy with awkward glasses scurries around the Bug — at the top tier of what looks like a wedding-cake. There’s a shot of the car’s tombstone seatbacks. The ad cuts to dumpy older women wearing cats-eye spectacles. They move nervously, adding to the suspense. When the time’s up, Gino claims there are no changes; VWs don’t change. He loses. A voiceover claims he was done in by 36 nice little changes that made the “program” possible.

This ad succeeds due to the content and the form. The form is televised nonsense but the content contains a verity. Gino fails, however, because he didn’t grasp VW’s advertising. He knows VWs never change just to change (an outright trashing of Detroit’s reason to buy), missing the flip side: VW refines its sameness. In a sense, this ad does something remarkable; it asks us to think about VW’s advertising and its car.

Isn’t the latter bit what’s often the problem with collector car publications and their presentation of auto ads? Ads are presented and read as if their only audience was the ideal consumer. Sometimes you must consider those who created ads. Their doings are just as interesting than the imagined lives of millions of hapless consumers of mass culture.

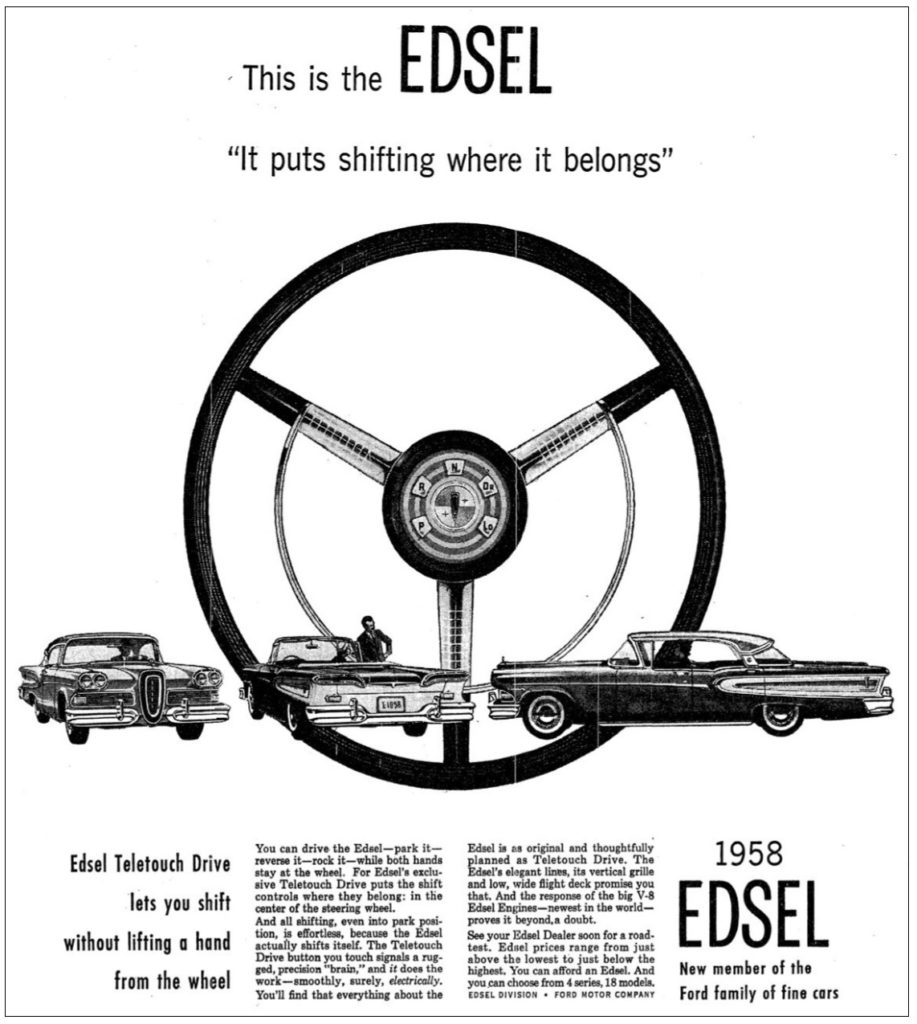

Ads, for example, have an institutional look. DDB’s advertising has a distinct tone, while adman Bruce Barton and his agency (BBDO) had a different one — the testimonial. Sixty years ago, adman Fairfax Cone was in the hot seat. His Edsel campaign flopped. Examine early Edsel ads and you’ll notice something unusual — they were monochrome just like Beetle ads. Cone was colorblind. In his memos, which I’ve read, he asks for monochrome artwork; he cannot approve color artwork. Color illustrations or photos, therefore, went to others. This is one reason why famous Cone-directed ads have a tasteful less cluttered appearance, he wasn’t into those busy colorful ad spreads.

Early Edsel ads reflected Cone’s aesthetic. I’ll say more about this later. Let’s say he couldn’t do much about the car. Remarkably, Cone landed the Zenith radio and TV account, at about the same time as the Edsel debacle. Classy monochrome ads worked for Zenith. And Cone’s “quality” emphasis didn’t fit the imperfect Edsel, but complemented Zenith.

Detroit’s dazzling dishpans

My biggest gripe is about collector-car publications is they don’t admit Detroit’s dazzling finned behemoths were monstrosities. They’re wonderfully awful. We don’t hear the loud voices of those who hated these cars and how they were sold. Design critics and consumer test publications pleaded with Detroit to start making sense. Herbert Marcuse, for instance, raised concerns about consumer-culture fraud. He said the Big Three determined his car’s beauty and covered cheapness; they gave it power and disguised its shakiness and made it work and its obsolescence.

Consumer Reports scolded the manufacturers. It told them to stop using consumers as guinea pigs. Similarly, you’d get the sense that consumers went wild for muscle cars; no one cared about fuel economy; gas was cheap. One look at 1960s sales figures shows VW rose to the top of the charts selling economy cars. And Toyota and Datsun grabbed a toehold because Detroit didn’t understand what drove people toward vehicles that weren’t wild animals.

60 years ago: Things changed

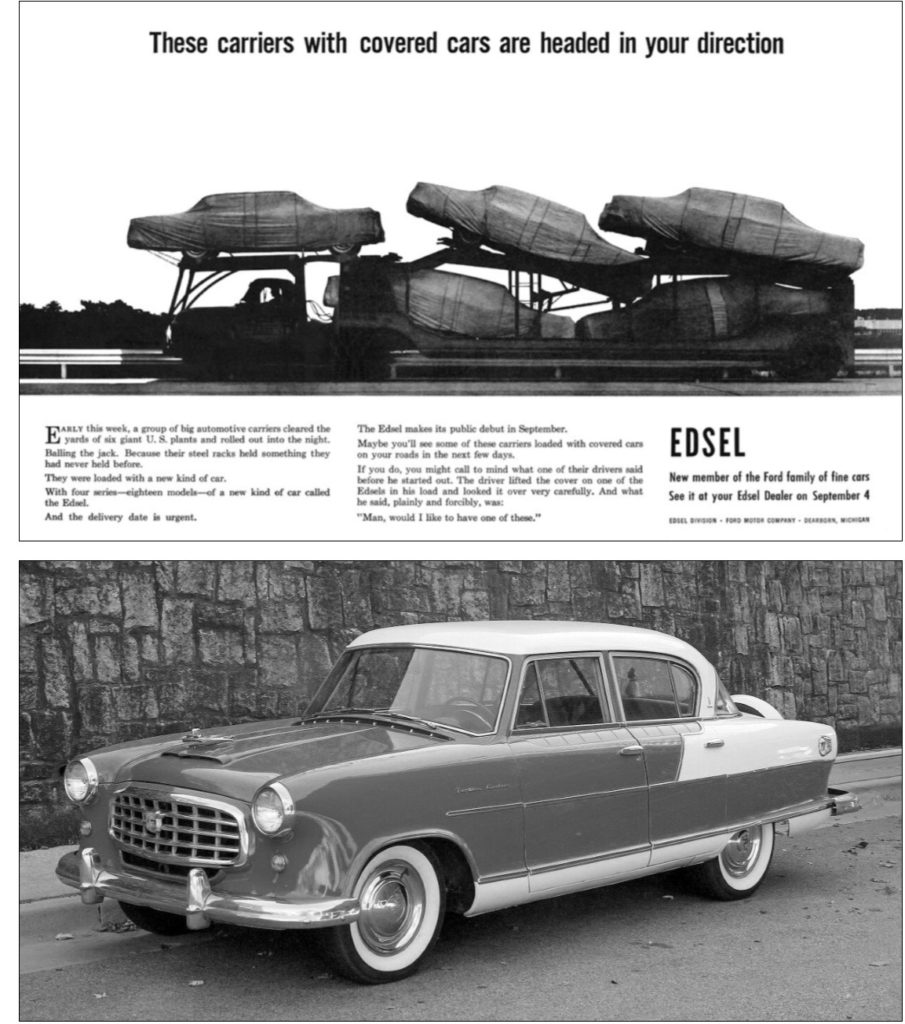

Sixty years ago, Ford killed the decoratively challenged Edsel, VW launched an advertising revolution and Detroit discovered the compact. I cannot let this milestone go unnoticed. It’s the anniversary of a remarkable shift in material culture. A moment when the fable of American postwar prosperity, concerns about conformity and just plain common sense hit critical mass.

In media studies, Ford’s Edsel caused a sudden collision in modern thought. Many scholars, and popular culture critics, thought the public was duped into wasteful want by the captions of consciousness: Madison Avenue. Ad men and women manipulated the public into buying more and more stuff. And that stuff came with chromium trim, triple-color schemes, greater size and wasteful power.

Intellectuals, who wondered how the Nazis shifted public opinion toward disastrous ends, argued persuasion via radio, print, film and later TV was the key. Some argued the hypodermic needle theory — just inject the public with enough messages and people were putty, malleable “vididiots” (for TV viewers) willing to accept your premise and behave accordingly. Scary.

During the postwar era, Americans seemed hellbent on buying jet-age inspired goods because hidden persuaders guided by marketing research and psychological tricks persuaded people to spend like there was no tomorrow on items obsoleted as quickly as Dior changed hemlines.

Then came the Edsel. Ford created a new car division offering 18 or so models decked out in everything an aspiring driver would want — except fuel economy, quality and sanity. Marketing studies, said Ford, proved it needed a mid-priced automobile to duke it out with GM’s Buick. Ford’s Mercury didn’t have the correct image. So take Ford/Mercury chassis/bodies, change their grilles and tail lights, add several gadgets and let marketing solve the problem.

Ford hired Fairfax Cone’s agency, FCB. Cone claimed advertising used two forms of motivation: the wish for owning the product and the brand’s image. His firm wasn’t known for automobile accounts but its slogans were famous: Clairol’s “Does she or doesn’t she?” Dial soap’s “Aren’t you glad” and Hallmark cards’ “When you care enough.” With successes like these, how could anything go wrong?

Everything! First, Ford researched the ideal buyer’s personality but forgot to test whether people wanted the car. To wit: dub the vehicle Edsel after Henry Ford’s son and then use the ad agency’s proposed names as models — Corsair, Citation, Pacer and Ranger. Copywriters winced. Dearborn’s fine family knew who Edsel was but not the American public — was it pretzel or no sell? Second, Ford expected mid-50s consumer demand to continue unabated. Third, it expected Americans to continue seeking ever larger more powerful cars (not ideal for the two-car family — a significant trend). Fourth, it believed most people who bought cars could be bought. Create a status symbol, present it as affordable elegance and advertise it like crazy.

Beginning in July 1957, the ad blitz commenced. Ads talked about a secretive all-new car built for you. Suspense increased. Ford prevented nearly anyone from seeing an Edsel before E Day— the official unveiling at dealerships in September. Meanwhile, automotive reporters and columnists, in August 1957, attended a swank Edsel party. Many returned from the Ford headquarters soiree filing stores praising the outstanding car. A Ford official claimed the Edsel was a hot property, like having Kim Novak.

On E Day, 2.5 million Americans flocked to Edsel dealerships. One Chicago suburban showroom was overwhelmed with at least 3,000 “lookers.” Unlike most 1950s fall car advertising campaigns, Edsel skipped the usual car at a slick showroom eyed by admiring glamorous people introductory TV or print ads followed by ads depicting happy families enraptured by a new set of turbine-inspired hubcaps or hidden gas caps. With this much hoopla, ad copy was, in contrast, surprisingly simple for a dazzling car.

Cone didn’t like the exaggerated visual and verbal claims of most car ads, so his magazine layouts had three horizontal bars. At the top was the headline: “This Is Edsel.” Under that, an illustration of the car and the bottom contained the copy. In retrospect, these uncluttered ads were laid out like VW’s.

Ad readership rankings showed Edsel’s September Life spread was the highest ever seen. Edsel dealers expected the car to sell itself. One-hour Edsel TV specials, with 50 million viewers, propped up showroom visits.

Consumer reaction to the Edsel, however, led to panic in Detroit. Ford hoped to move 600 cars a day but in November, 222 were sold daily with demand plummeting. (Note: VWoA sells fewer than 300 Passats a month.) In addition, Edsel buyer surveys revealed unhappy owners. Consumer Reports devoted pages to the entire Edsel affair. The car it bought was a lemon — proof that Detroit’s dishpan was a defective dud.

A recession in 1957 weakened demand for medium-priced vehicles. Small, inexpensive foreign car sales boomed, with VW’s evergreen Beetle in short supply. Ramblers sold well. Ford’s Robert McNamara, who didn’t support the E-car program, blew a fuse. During a meeting with ad men, he ransacked a room, ripping Edsel ads from the walls and claiming they were all wrong.

Cone lost control of the account. His dignified-car theme dived, replaced with another set of ads claiming this really new car was low priced, too. Edsel, they asserted, was going to be copied. Cone claimed the campaign was “confused.” For 1959, Edsel’s slogan was “Making history by making sense.” Ford axed several Edsel models, and its powerful V-8 engines got six-cylinder alternatives. The gig was over.

The Edsel fiasco was an example of what the Wall Street Journal dubbed “The Mistakes”: heavily promoted new products that flopped. Hidden persuaders and their hypo-needle advertising did not manipulate consumer demand. The powers of mass persuasion weren’t so potent. To a large extent, America’s postwar shopping spree wasn’t driven by non-stop promotion of Dagmar bumpers, Buick portholes and Cadillac tail fins. Increasingly affluent Americans bought lots of things. Often other factors shaped consumer culture with supermarkets and discount stores the new battle lines for brand competition. And what Wilbur Shaw described as the homeliest car in the world, a small car that would never sell over here became America’s cherished Bug.

Beep-beep

If you turned on your TV set for the 1959-1960 season, chances are you witnessed a plucky little car with balloons tied to it (better to see it in NYC traffic shots), zipping in and out of parking spaces and drinking thimbles of gas instead of gallons. Even the engine was easy to rebuild. All capped by a get-one-everyone-is-driving-it audible BEEP-beep signature.

This ad had everything Television magazine said was required to make Americans accept the small car — lots of happy people motoring in the latest motoring fashion. But it wasn’t a VW ad. No, the twin-beep happy ads were Renault’s — VW’s chief competitor. Those beeping ads (Renaults had two horns) couldn’t save Renault. For a number of reasons, including lousy distribution (dealers) and poor reliability, Renault faltered.

It later ran a VW-like ad confessing that its cars and dealers came up short. Underneath a bold quote, “I won’t buy a Renault no matter how good it is,” it claimed Renault and its drivers did a lot of swearing. The new R 10, however, fixed what needed fixing. The copy took a jab at VW by saying some people are turned off by all inexpensive small cars due to a certain hard-riding noisy small vehicle, which we all know. It then swore its new model would stop the swearing. This ad couldn’t stop Renault-fueled foul talk.

VW’s 1959-1960 print ads launched a revolution in American advertising — and their frank conversational tone, self-reflexiveness (outright confessions of admen) and admissions of imperfections (product or the ads themselves) reverberated. The story is better than fiction. Here we have a Nazi-tainted automobile, which became the emblem of the postwar German economic miracle — proof that the West could outdo the Soviets for the minds and purses of postwar Europeans. In a sense, VW represented an ideological defense line just miles from the East German border.

VW’s offbeat car gradually caught on with American drivers. It wasn’t love at first sight. Yet, it gained a reputation as correction of what was wrong with the American automobile. Instead of annual styling changes, ever increasing rear wings and plus sizing that didn’t fit on prewar driveways and into garages, the Beetle received several mechanical refinements. These better yet sparsely equipped Beetles were nicely finished and attractively priced. Service and parts mattered, too.

According to VW lore, Detroit’s onslaught of compacts planned for the fall of 1959 led VW to seek an ad agency. It chose one without a proven record in automobiles. That’s gutsy. It went with Doyle Dane Bernbach, an agency that broke a lot of conventions, both in the ads themselves and the firm’s organization. It was creative. And Jewish. Yep, Jewish admen wrote the copy for what was to them an emblem of a very dark and not very distant past.

Yet, their creative work broke through advertising clutter — much like Pedro Almodovar’s films rampaged 1980s social norms. They took mass society concerns, the sense of being cheated by advertising, planned obsolescence and forced conformity and offered the VW car or its advertising sensibility as a corrective — feeding on postwar consumer discontent.

Even my North Dakota grandmother got it. She posted a gasoline ad on her board next to her kitchen phone. Its illustration depicted a very little car towing an enormous yacht. This fuel supposedly provided greater power. My grandmother, however, wrote the words “status symbol” underneath her clipping.

Her mode of transport: a Detroit land yacht, a used 1969 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. ![]()

Cliff Leppke | leppke.cliff@gmail.com

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE:

- A LOOK BACK: 2019 was chock full of automotive news, and Cliff Leppke has a list of high- and low-lights.

PLUS OUR REGULAR COLUMNS AND FEATURES:

- Small Talk – VW + Audi at a glance

- Retro Autoist – From the VWCA archives

- The Frontdriver – Richard Van Treuren

- VolksWoman – Lois Grace

- Parting Shot – Photo feature

- Local Volks Scene – A snapshot of local chapter activities

- VW Toon-ups – Cartoon feature by Tom Janiszewski

LOGGED-IN MEMBERS CAN SEE THE ENTIRE AUTOIST ISSUE BY CLICKING ON THE COVER PHOTO ABOVE.